If National Treasury doubled the excise duty on sugary cooldrinks from the current level of around 10% to the 20% that experts proposed when SA first raised the subject back in 2013, it could raise billions of additional revenue to help fund the fight against Covid-19.

This is the view of Karen Hofman, director of the South African Medical Research Centre for Health Economics and Decisions. The level of around 20% is also advocated by the World Health Organisation (WHO).

INSIDERGOLD

Subscribe for full access to all our share and unit trust data tools, our award-winning articles, and support quality journalism in the process.

The current health promotion levy (HPL) imposes a tax of 2.21 cents per gram of sugar in beverages that contains over 4 grams per 100 millilitre, which amounts to a tax rate of approximately 10% to 11%. The current levy adds about 46 cents to the price of an average can of cooldrink.

Although the so-called sugar tax was only introduced two years ago, figures show that it is working. “And the huge job losses that industry predicted did not happen,” says Hofman.

The bottom line is that the addition of tax on unhealthy products – like tobacco, alcohol and cooldrinks that contain a lot of sugar – increased their prices and people bought less.

Quoting several surveys, Hofman says that the purchase of sugary drinks declined by 51% by volume and sugar intake decreased by 29%.

A study in Soweto found that teenagers and adults that used to consume a lot of sugary drinks, reduced their consumption from 10 cooldrinks per week to only four after the first year of the sugar tax.

These figures are significant if one considers the prevalence of obesity, as well as its dangers and associated costs.

“Obesity rates in SA are rising. In 2018, 15% of men and almost 40% of women were obese, or 27% of the total population,” says Hofman, adding that children who drink a tin of cooldrink every day are 55% more likely to develop obesity, and 70% of them will became obese adults.

Obesity is one of the top risk factors that leads to premature death from cardiovascular disease and diabetes, which together account for 51% of all deaths in SA.

During a discussion organised by the Healthy Living Alliance (Heala), Hofman explained that it is in particular sugar in liquid form that increases the risk of obesity, diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, many forms of cancer and teeth decay.

She says medical and indirect costs associated with diabetes and hypertension are huge, mentioning a figure of some R13.2 billion per annum.

SA cannot afford this. Government spending on healthcare was budgeted to increase from just over R190 billion in the 2017/18 tax year to more than R240 billion last year, before additional spending due to the Covid-19 pandemic, which is bound to continue this year too.

Heala points out that global experience has shown that being obese increases the risk of dying from Covid-19 by almost 50% and more than doubles the risk of being hospitalised.

Hofman says that the sugar tax not only promotes better health, but also raised R5.4 billion in tax revenue for government since its introduction. This would have been enough to finance SA’s initial payment for Covid-19 vaccines from the Covax facility almost 20 times over, according to Heala.

In addition, Hofman advocates that government increase the tax rate on sugary drinks to 20% and extends it to fruit juice too – to raise more money and to make SA healthier.

“Fruit juice is not a healthier option. It contains even more sugar than cooldrink. We should rather eat our fruit,” says Hofman.

“Excise duties work,” says Corné van Walbeek from the Research Unit on the Economics of Excisable Products at the University of Cape Town, referring to the age-old economic principle that people respond to incentives.

He says that excise duties change consumer behaviour, as well as that of producers, if designed properly and implemented effectively.

He presents decades’ worth of data to prove the effectiveness of excise duties, referring to taxes on alcohol and tobacco. Very interestingly, he mentions that income tax did not exist for ages, but that tax has been levied on specific products for centuries.

Changes in tax on alcohol

The early 1990s saw an important change in the focus of excise duties, says Van Walbeek. “The aim of these taxes changed from that of collecting revenue to changing consumer behaviour.

“In the case of alcohol, the tax structure was changed from taxing the volume of the drink to a tax based on alcohol content. Since 1990 the taxes were raised sharply,” says Van Walbeek.

Excise duties on beer, spirits and on cigarettes

Source: Research Unit on the Economics of Excisable Products, University of Cape Town

It had the desirable effect. Van Walbeek’s figures show that the consumption of cigarettes declined significantly, while that of alcohol declined from around the equivalent of nearly 10 litres of pure alcohol per person per annum in 1997, to less than 8 litres currently.

“The increase in prices had a very real effect on consumption, while it also changed production. Producers had the incentive to reduce alcohol content,” says Van Walbeek. He mentioned that spirits with an alcohol content of around 38% are becoming more common compared with the norm of 43% alcohol a few years ago, while all the major beer brewers offer light beers with lower alcohol content (around 4% compared with the usual 5%).

The effect of tax on cigarettes was more profound, because the taxes are much higher. Total tax payable on a packet or 20 cigarettes is currently R17.40, including VAT. On some brands, the tax is equal to 80% of the purchase price.

Rise and fall of cigarette use

Source: Research Unit on the Economics of Excisable Products, University of Cape Town

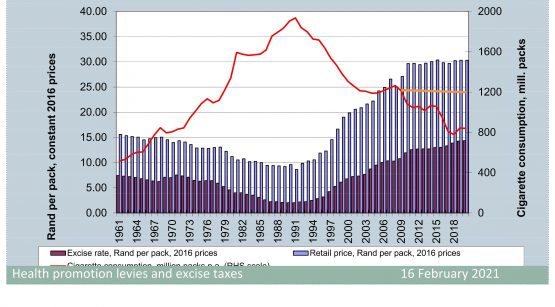

Cigarette consumption increased strongly from 1960 to 1990, because excise duties and selling prices decreased steadily in real terms. Van Walbeek’s figures suggest that cigarette consumption increased nearly fourfold from 1960 to 1990.

Government changed its stance from 1994, setting itself the goal to reduce cigarette consumption and duties increased sharply. Consumption fell by more than 50%.

Van Walbeek admits that the increase in duties, especially on cigarettes, stimulates illicit trade. His figures suggest that illicit trade in SA increased to 400 million packets per annum, or around one third of total sales. He says that illegal sales were “off the charts” during the tobacco ban in 2020.

Tax expert Michael Sachs, former head of national treasury’s budget office, agrees. He says that one needs to be careful about “perverse changes” such as the illegal cigarette trade due to high excise duties.

He says the key to success is to design the correct tax structure, such as targeting sugar and alcohol content in beverages. And a blanket tax on cigarettes: “All cigarettes are bad,” says Sachs.

Taxation is political, says Sachs, but there is no doubt that government is facing a funding crisis and there are unusual pressures on the health sector, justifying health taxes.

Heala is pushing for an increase in excise tax on bad products. Heala head Lawrence Mbalati says that government would net around R2 billion to help fund the fight against Covid-19 it treasury doubled the health promotion levy to the 20% that was originally proposed.

“This is a watershed moment for the country,” says Mbalati explains. “Government revenues are under immense pressure and funding the fight against Covid-19, including vaccines, remains critical.

“An increase in the health promotion levy to 20% will raise additional revenue in the short-term. In the long-term, we know that a health promotion levy of 20% will reduce the amount of sugar people eat, decreasing their chance of developing conditions such as diabetes, obesity and high blood pressure that also put people at a higher risk of dying from Covid-19,” says Mbalati. Heala also believes that the levy must be extended to include fruit juice.

“The health promotion levy has been an outstanding success. We want a healthy society and the tax proved to be an effective incentive. People reduced their sugar consumption and producers reduced sugar content and product sizes,” says Sachs.