State and local tax deductions

Prior to the enactment of the Tax Act 2017, individuals had no direct limit on the amount of state and local taxes they could deduct on their federal returns.4 The deduction was available to households showing deductions that accounted for 27 percent of taxpayers in 2017 . The other 73 percent took the standard deduction.5 Of the households broken down, 93 percent took the SALT deduction.

The SALT deduction had the effect of softening the blow from state and local income, property and sales taxes. For example, New York taxpayers in the 33 percent federal class in 2017 who paid $ 30,000 in state and local income and property taxes could cut their federal taxes by $ 10,000. The federal government essentially granted them a discount of this amount.

In California, high-income taxpayers subject to the federal tax rate of 39.6 percent and a state tax rate of 13.3 percent were only exposed to a state tax rate of 8.0 percent due to federal deductibility. The higher the household income, the greater the effective federal grant.

The Tax Act of 2017 changed this. Most higher-income taxpayers will now face the full burden of state and local taxes – the full cost of $ 30,000 in New York and the full 13.3 percent tax rate in California.

Prior to the change in the law, federal deductibility subsidized high-tax countries and encouraged them to load their taxes on higher-income individuals. The SALT deduction "shifted the tax burden of the jurisdiction to those best placed to receive the federal tax subsidy," who were high earners because they were generally the ones who made a listing

Taxes are the “price” residents pay for state and local services like police and schools, but the SALT deduction has effectively lowered that price and caused residents to overcharge. The Congressional Budget Office noted the SALT deduction: "Because of the subsidy, too many of these services can be provided and state and local governments may be larger as a result." 7

The previous SALT deduction mainly benefited higher earners. Before the amendment to the law, 91 percent of the benefits went to households with an income of more than 100,000 US dollars.8 Countries benefiting from the deduction had higher incomes and higher taxes than other countries. In California, 96 percent of state and local deductions in excess of $ 10,000 were made by households with incomes greater than $ 100,000.9

The new SALT limit is a reform that has long been necessary. In the run-up to the 1986 Tax Reform Act, the Reagan administration proposed removing the deduction, and President Reagan argued, “If high-tax countries didn't have this federal crutch to sustain their high spending, they might have to cut taxes to stay competitive . “10 The 1986 Act eliminated sales tax deductibility, but Congress added that deduction in 2004.

The 2017 law capped the SALT deduction for both single and married taxpayers to $ 10,000 per year. It also nearly doubled the standard prints. These changes will reduce the number of SALT deductions from 42 million in 2017 to 17 million in 2018.11 For those who continue to use them, the average benefit will be less than half. The $ 10,000 cap is not adjusted for inflation.

The full weight of state and local taxes will now be felt by an additional 25 million households. The states where SALT deductions were largest as a percentage of income were New York, New Jersey, Connecticut, California, Maryland, Oregon, Rhode Island, Massachusetts, and Minnesota.12 These are generally high-tax states.

Governments in high-tax countries are concerned that the SALT reform will encourage additional high-income taxpayers to move out. If they move in significant numbers, it would be a blow to national budgets. In New York, the top 1 percent of the highest earners pay 41 percent of state income taxes. In New Jersey, the proportion is 37 percent.13 In California, the top 1 percent pay a remarkable 50 percent of state income taxes.14

According to the new federal law, some states are becoming more cautious about increasing taxes. New Jersey lawmakers passed five laws under former Governor Chris Christie to increase taxes on millionaires. Christie vetoed them. But now that New Jersey has a governor eager to collect taxes on millionaires, lawmakers have shied away. Senate President Steve Sweeney (D), who previously advocated higher taxes, warned earlier this year: "This state is taxed," and federal tax law "changed the game for us." 15 But in July Sweeney relented and agreed that the governor should raise the highest individual income tax rate from 8.97 percent to 10.75 percent.

To protect themselves from the SALT changes, some states are considering converting some of their mostly non-deductible income taxes into deductible wage taxes for the employer. Other states are trying to convert government tax payments into charitable contributions that are still fully deductible. New York has limited versions of these mechanisms in place, but the regulations may not be effective or exist under federal tax law. The US Treasury Department released a notice stating that it will impose regulations.

A more productive response to federal tax changes would be for high-tax countries to lower their tax rates so people have less incentive to migrate. State policymakers should use federal tax reform as an opportunity to rethink their national budgets to ensure residents receive quality services at minimal cost.

Will more people move to states with higher taxes in states with lower taxes under the new federal tax law? The next section looks at current migration trends for some pointers.

Trends in interstate migration

This report examines interstate migration data produced by the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) .16 The IRS flags when a taxpayer's address changes and has created a database that summarizes movements to and from each county and state are. The database contains the adjusted gross income (AGI) of each taxpayer.

The IRS data shows that 2.8 percent of taxpayers – essentially households – moved between states in 2016. Taxable households can be either singles or married couples with or without children. An average household is 2.1 people in the IRS data. 17

The IRS data does not include households that do not file tax returns, missing about 13 percent of the population.18 However, the data is reasonably accurate because it is not based on survey data, as is migration data obtained from the US census office.

Experts agree on the fundamentals of interstate migration.19 The rate of migration has declined since the 1980s, although the IRS data shows a smaller decline than the census data.20 The internal migration rate in the US is higher than most other countries with high income countries. Migration rates decrease with age. Tenants are more likely to move than homeowners. Singles are more likely to move than married couples. The migration is a bit procyclical.

Table 1, column 1, shows the number of net domestic immigrants (immigrants fewer emigrants) for each state in 2016 based on IRS data. All data in this report excludes international immigration and emigration.

New York lost 218,937 households to other states in 2016, gained 142,722 households from other states, for a net loss of 76,215.

The other states with the largest net migration losses were Illinois (41,965 households), New Jersey (25,941), California (25,913), Pennsylvania (19,516), Massachusetts (14,549), Ohio (13,254), Connecticut (12,254), Maryland (12,068)) and Michigan (10,325).

Where did these native migrants go? The largest net inflows went to Florida (95,072), Washington State (30,480), North Carolina (25,601), Colorado (24,672), Arizona (24,211), Oregon (21,729), Texas (19,414), South Carolina (18,519), Georgia ( 17,798) and Nevada (14,236).

For almost all countries, the migration flows in 2016 represent expanded trends. For 48 of the 50 countries, the net migration direction (in or out) in 2016 corresponded to the direction of the total net flows in the last five years. The two states that were different were oil producers Oklahoma and North Dakota, which used to have net immigration but are now net exodus. Also note that Texas had unusually low immigration in 2016 – its net inflows have been larger than Florida for the past five years.

In many countries, the latest trends go back decades. The biggest net migration losers between 1993 and 2010 were New York, California, Illinois, Michigan and New Jersey. The top net immigration winners over the period were Florida, Arizona, Texas, North Carolina, and Georgia. 21

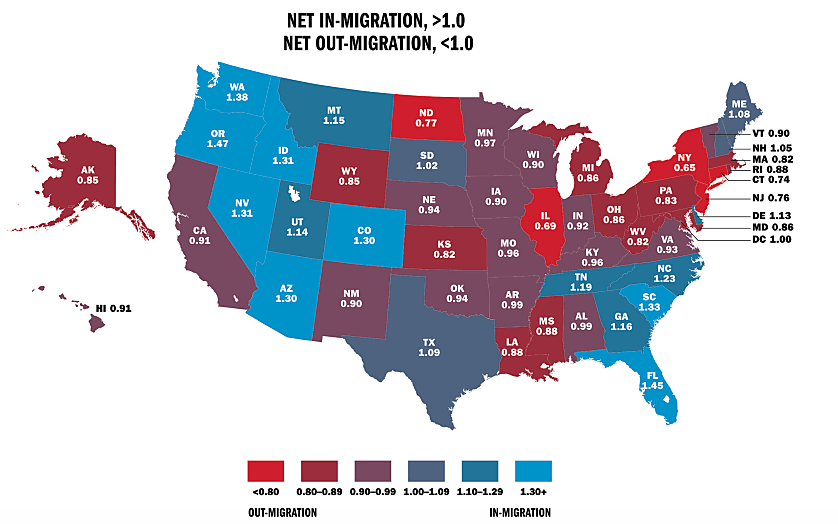

Table 1, column 2, shows the ratio of gross immigration to gross emigration in 2016. Countries that are losing their population have ratios of less than 1.0. States that are growing in population have ratios greater than 1.0. The New York ratio is 0.65, which means that out of 100 households left, only 65 have moved in. Florida's ratio is 1.45, which means 145 households out of every 100 remaining households moved in.

Table 1: Interstate migration flows, 2016

Source: Author calculations based on data from the Internal Revenue Service.

The IRS database has AGI in place so we can see how much total income is migrating between states. The AGI is the income reported in the first year that a household is at a new address. In fact, AGI does not migrate. People do. A person's income can be higher or lower after moving to a new state. The statement that income “migrates” is, however, a rough abbreviation for the fact that the earning power of households fluctuates between countries.22

In 2016, households with incomes of $ 227 billion moved between states. In Table 1, Column 3, New York lost $ 8.4 billion in net income to other states in 2016, while Illinois lost $ 4.8 billion. Florida won $ 17.2 billion.

The relationships in column 4 are similar to those in column 2, with the exception that they are income relationships, not households. The Florida household rate is 1.45 and the income rate is 2.46. The higher income quota means that immigrants to Florida have a much higher income than expatriates. Other states with income rates much higher than the household rate are Idaho, Montana, South Carolina, Utah, and Wyoming. These states attract large numbers of high-income immigrants compared to their emigrants.

If the ratio in column 4 is lower than the ratio in column 3, it means that the government has net emigration, particularly from households with higher incomes. Connecticut is a good example.

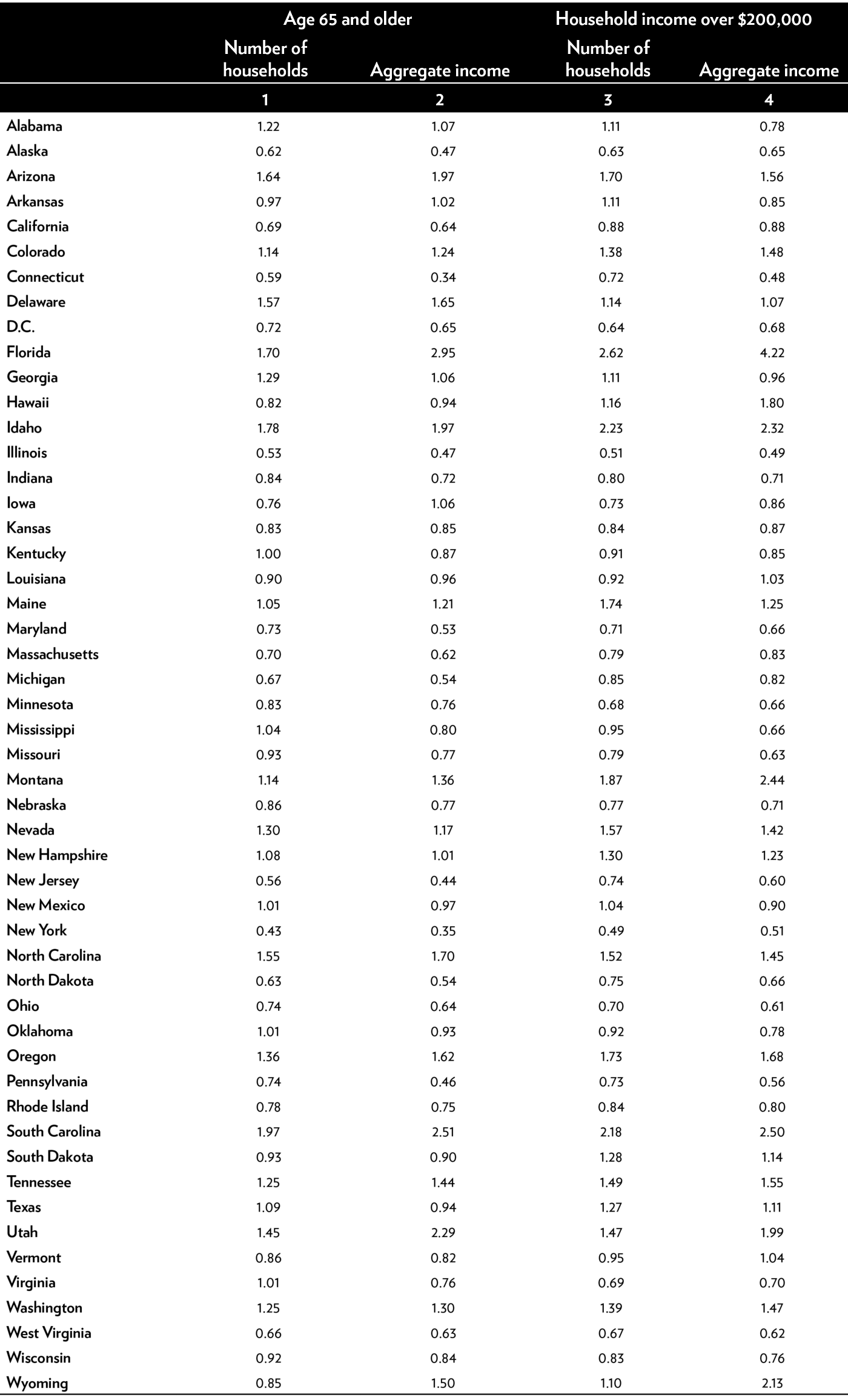

Table 2 shows the net migration rates for households with people aged 65 and over and for households with an income of more than US $ 200,000. Some of the places that both seniors and high earners leave on the internet are Alaska, California, Connecticut, Illinois, Maryland, New Jersey, New York, North Dakota, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia. Some of the places the two groups are moving to on the internet include Arizona, Colorado, Florida, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, North Carolina, Oregon, South Carolina, Tennessee, Utah, and Washington State.

Table 2: Ratio of immigrants to emigrants, senior citizens and high earners, 2016

Source: Author calculations based on data from the Internal Revenue Service.

Why do people move?

In an annual survey by the Census Bureau, individuals moving any distance are asked of 19 choices as the main reason behind their decision. The most popular decisions in 2017 were “looking for a new or better home” (16.0 percent), “starting your own household” (11.5 percent), “other family reasons” (11.3 percent), “new job or job transfer” "(9.9 percent)) and" wanted cheaper housing "(8.3 percent) .23

The Census Bureau does not ask moving companies about taxes. However, some of the 19 options may reflect the impact of taxes. For example, people moving for residential purposes may consider the amount of property taxes, as those taxes are a standard item listed in residential property sales notices. Similarly, people moving for new jobs may consider the impact of income taxes when moving between a high-tax state like California and a non-income state like Nevada, for example.

A national survey by Bankrate found that taxes play a major role in deciding where to retire.24 Based on their survey, Bankrate weighted the factors for location choice as follows: cost of living (20 percent), taxes (20 percent), quality of Health care (15 percent), weather (15 percent), crime (10 percent), cultural vitality (10 percent) and well-being (10 percent). Bankrate found that 47 percent of Americans would consider moving when they retire.

Figure 1 shows that many people move from northern states to southern states. Liberal analysts usually attribute this fact to people who want to live in warmer states. Conservative analysts usually attribute this to people wanting to live in lower-taxed states. If one looks at the survey data of the Census Bureau only for international moves, only 2.2 percent of the 19 possible choices chose “climate change” as the reason for moving.25 That is surprisingly low. Apparently, the popularity of many southern states is more than just higher temperatures.

Figure 1: Interstate migration flows, immigrant to emigrant ratio, 2016

Source: Author calculations based on data from the Internal Revenue Service.

Americans move to states with lower taxes

Americans are moving in significant numbers from higher-taxing states to lower-taxing states. This is evident from the raw migration data discussed here.

According to the Census Bureau, state and local tax receipts averaged 10.1 percent of personal income in the nation in 2015.26 Sales taxes were 3.5 percent, property taxes 3.1 percent, individual income taxes 2.4 percent, and the Corporate and other taxes 1.1 percent percent. Sales taxes include general sales taxes and selective sales taxes on products such as gasoline, alcohol, and cigarettes.

Which of these taxes could influence individual migration decisions?

Polls asked Americans about their “least popular” taxes.27 The least popular state and local tax has long been property tax. After that, Americans will no longer like sales taxes and individual income taxes. Other surveys have asked which taxes are the least “fair”. Real estate and various selective sales taxes are often the main responses, followed by individual income and general sales taxes.

Hence, sales, property, and individual income taxes are likely to have the greatest impact on migration decisions as they are the largest state-local taxes and the least liked. Corporate taxes are less likely to be rejected in polls, which is not surprising as they are less visible to the public.

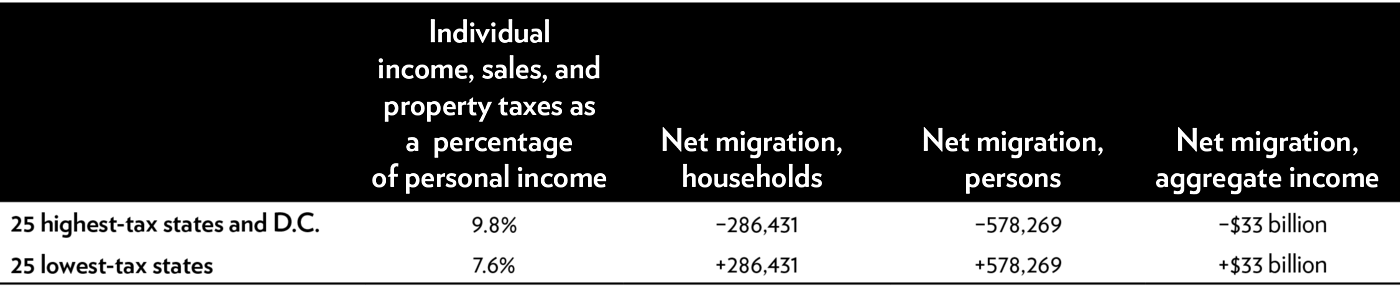

Table 3 shows data for the combined net migration flows for the 25 countries with the highest and 25 with the lowest taxes. Taxes are measured as state and local sales, property, and individual income taxes as a percentage of state personal income. In 2016, a net 578,269 people moved from the highest-taxed states and the District of Columbia to the lower-taxed states. Of the 25 countries with the highest taxes, 24 had net emigration. Of the 25 countries with the lowest taxes, 17 had net immigration.

Table 3: Net migration from high-tax to low-tax countries, 2016

Source: Author calculations based on data from the Internal Revenue Service.

The tax gap between the 25 highest and 25 lowest states does not seem to be large at 2.2 percentage points of income. However, many of the largest migratory flows take place between the countries with the highest and lowest taxes. The largest drainage state, New York, has a tax burden of 13.0 percent, while the largest inflowing state, Florida, has a tax burden of 6.6 percent.

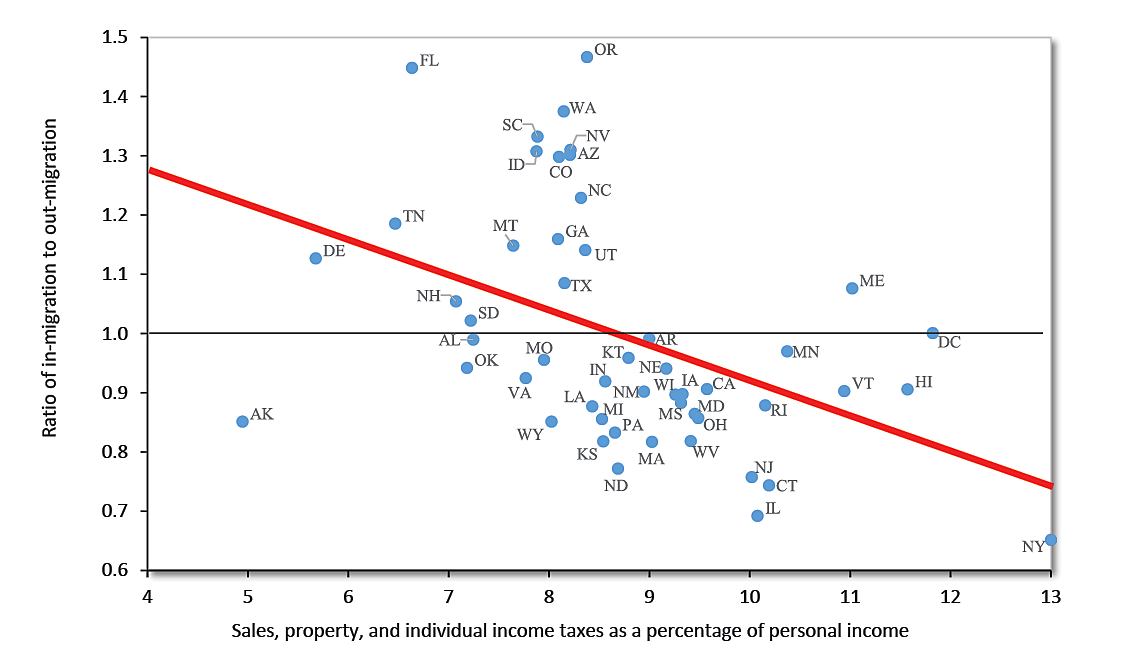

Figure 2 shows the relationship between tax levels and migration rates. The migration rates are taken from Table 1, Column 2. The tax variable is the average state and local sales, wealth, and individual income taxes as a percentage of personal income.28

Figure 2: Tax levels and net migration rates, 2016

Source: Author calculations are based on data from the Internal Revenue Service and the US Census Bureau.

The figure shows a clearly negative relationship between tax level and migration. On the left, states have lower taxes and net immigration (a ratio greater than 1.0). On the right, states have higher taxes and net emigration (a ratio of less than 1.0).

There were 17 countries that had net immigration in 2016 (a ratio of more than 1.0). Of these, 17 had a tax burden of less than 8.5 percent.

Of the 26 states with a tax burden of 8.5 percent or more, 25 had net emigration. The only high-tax state with immigration was Maine. (The District of Columbia had a migration rate of 1.0.)

Figure 2 shows a fitted regression line. A simple regression of the migration ratio for the control variable leads to a statistically highly significant adjustment. The F statistic (12.1) and the t statistic (3.5) are significantly above the 99 percent level. The state tax level and net migration flows are strongly correlated.

Here are some patterns in interstate migratory flows: 29

- The northeast. New Hampshire had net immigration for four of the last five years on the IRS data (2012-2016). It is a low tax state with no income tax or general sales tax. Nearby, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Vermont all suffered net churn every five years with higher taxes. New Hampshire enjoys net immigration from all three states.

- The mid west. South Dakota has seen net immigration in four of the last five years. In contrast, neighbors Nebraska, Iowa, and Minnesota, with higher taxes, had net churn every five years and migration deficits each with South Dakota. South Dakota is one of the lowest tax states and has no income tax.

- The southeast. Kentucky has seen net emigration for the past five years, while Tennessee has seen net immigration every year, including from its neighbor. Kentucky is a relatively high tax state, while Tennessee is one of the lowest tax states and has no income tax.

- The West. The top three destinations for California expats in 2016 were Texas, Washington State, and Nevada – all low-tax states with no income tax. California has a large migration deficit with all three states.

An interesting pattern affecting high-tax countries across the country is that the net migration rate is deteriorating for older age groups. For example, in California, the migration rate for people ages 26 to 34 is 0.92, while the ratio for people ages 55 to 64 is 0.60.30. Connecticut, Illinois, Maryland, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New Jersey, New York, and Ohio show the same pattern. It seems that older people with higher incomes and higher taxes are even less willing to move to such states than young people with lower incomes and lower taxes.

Taxes are more likely to affect movements when interstate disparities are large – and disparities between states with the highest and lowest taxes are large. The District of Columbia government produces an annual study comparing state and local taxes for hypothetical households with different income levels in each state's largest city.31 The study includes sales, property, individual income, and vehicle taxes.

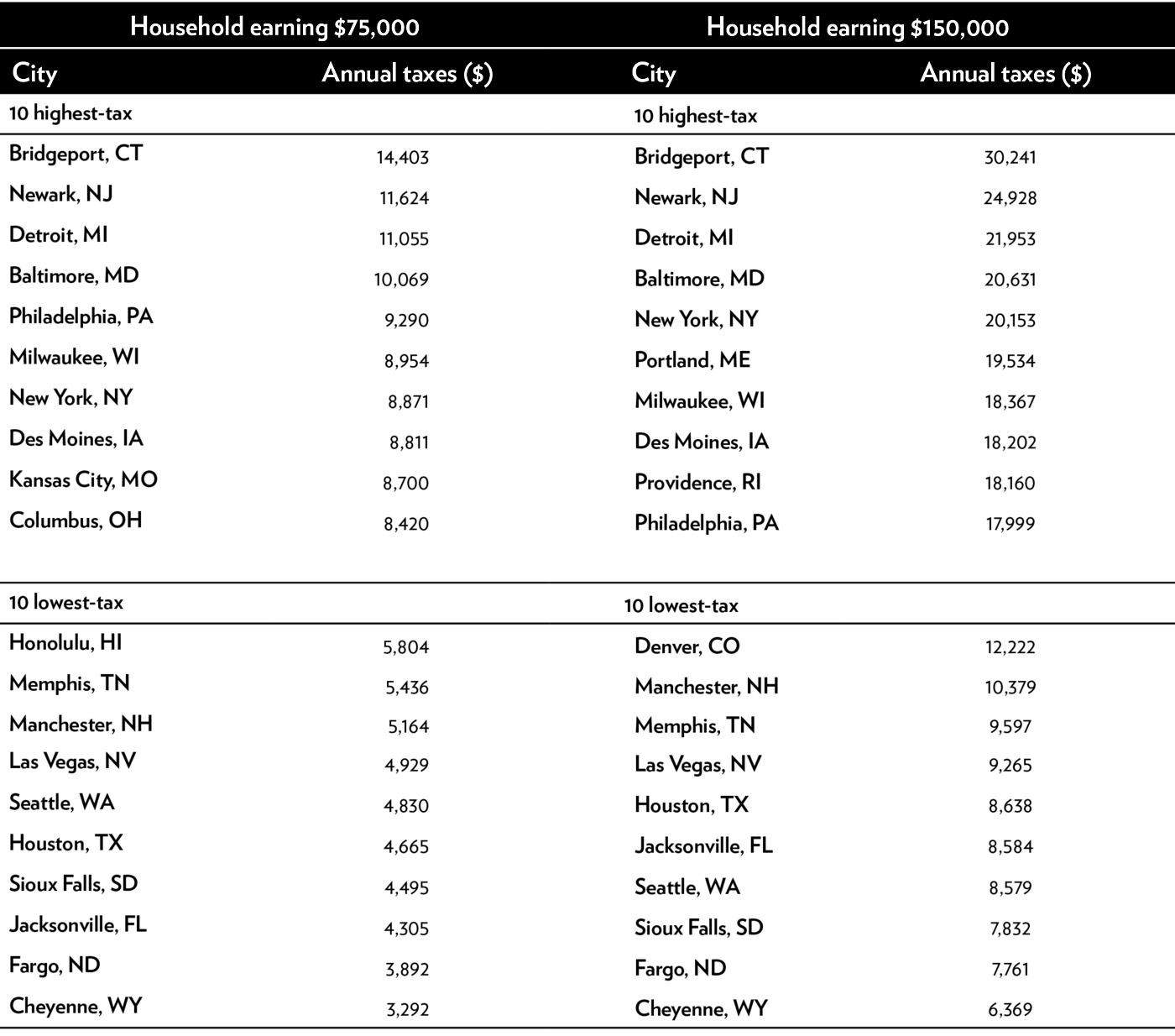

Table 4 shows some of the results. Families earning $ 75,000 a year could save about $ 5,000 a year by moving from a high-tax city to a low-tax city. Families earning $ 150,000 could save about $ 10,000 with such a move.32 These differences seem big enough to induce some people to move.

Table 4: Household taxes for the largest city in each state

State and Local Sales, Real Estate, Individual Income, and Road Taxes, 2016

Source: District of Columbia Government, "District of Columbia Tax Rates and Charges: A Nationwide Comparison, 2016," December 2017.

People considering moving can easily find out about government tax differentials. Two recent Kiplinger.com articles were “Best States to Move to in 2018 for Lower Taxes” and “Top 10 Most Tax-Friendly States in the US.” 33 Another resource is WalletHub's “2018 Tax Burden by State,” in which income and Sales are compared, property taxes and excise taxes. 34

Of course, many other factors influence interstate migration, and these factors are complex and sometimes interrelated. When high taxes in a state buy quality services like good schools, those services will attract migrants who are willing to accept the higher taxes. However, there is no clear link between the level of taxation and the quality of government services in individual states.35 In some states, tax revenues can be used efficiently to pay for high quality services that residents and immigrants want. In other countries, tax revenues can be distributed among expensive bureaucracies or misallocated to activities that most people do not want.

Most people probably consider a combination of factors when moving. A recent CNBC article ("Californians Fed Up on Housing and Taxes Flee the State in Large Numbers") suggests that high housing, tax and gasoline costs have driven people out of California.36 Costs of comparable housing Los Angeles has twice as much Angeles as Las Vegas and Phoenix, and gasoline is a dollar a gallon more expensive in California than in Texas, in part because of taxes.37 Though California is considered perhaps the most beautiful weather in the nation, California has suffered domestic failures suffered. Migration for many years.

Economists have used regression analysis to determine the specific factors driving interstate migration. However, research has not found clear answers when it comes to taxes – numerous studies have found significant migration effects, but some have not.

Since the 1970s, economist Richard Cebula has published statistical studies attributing interstate migratory flows to a number of factors, including government economic growth, housing costs, taxes, climate, crime rates, and public school spending.38 Cebula has consistently determined this income and property tax burdens are statistically significant for those Declaration of interstate migration.

For example, a 2012 study by Cebula and Usha Nair-Reichert performed regression analyzes on the determinants of interstate migration between 2000 and 2008.39 They found that government controls employment growth, unemployment, January temperatures, spending on education, and the cost of living Per capita income and property taxes were important in explaining migration. Their results confirm the Tiebout Hypothesis that people “vote with their feet” and move to jurisdictions that offer better tax deals.40

Numerous other statistical studies have found that state and local taxes affect interstate migration, including that of Mark Gius; Yu Hsing; Robert Preuhs; Karen Conway Smith and Andrew Houtenville; David Clark and William Hunter; Antony Davies and John Pulito; and Roger Cohen, Andrew Lai and Charles Steindel. 41

New Jersey increased its highest individual income tax rate from 6.37 percent to 8.97 percent in 2004. A statistical study by economists for the state Treasury found that the increase resulted in net churn of 80 millionaires or more per year.42 That would be a modest effect, but drain would add up over time if sustained.

With federal deductibility, the 2.6 percentage point increase in New Jersey in 2004 was an effective increase of 1.6 percentage points. By comparison, the 2017 Tax Act ended deductibility for most taxpayers, increasing New Jersey's highest effective income tax rate by 3.6 percentage points.43 In 2018, New Jersey increased its highest individual income tax rate from 8.97 percent to 10.75 percent We should expect larger outflows in the coming years than after 2004.

Economists Cristobal Young and Charles Varner found a smaller effect of the New Jersey tax hike in 2004, and Young and co-authors of other studies found that taxes had little effect on interstate migration of millionaires.44 The authors argue that millionaires are not particularly footless because they are "embedded" in their communities. That is, they often have social and business relationships in their states that make it difficult to move.

Overall, numerous statistical studies have found that taxes affect interstate migration, but some studies have found opposite results. One reason for the mixed results could be the “capitalization” mechanism. A tax increase in one jurisdiction can lead to an initial move to another jurisdiction. This flow will decrease property values in the tax-increasing jurisdiction and increase property values in other jurisdictions. These changes in property value will ultimately stem the flow of migration as the economy enters a new equilibrium. If differences in state taxes are mainly capitalized, the associated migration flows will be reduced.

Wage adjustments can also offset the migration effects of taxes.45 An increase in income tax in a state can cause individuals to emigrate over time. In this case, gross wages in the tax-increasing state would increase compared to other states, and this would ultimately curb the outflow.

A variety of political and convenience differences between states – not just taxes – can be capitalized in asset prices or offset by gross wage differentials. As these market adjustments are made, the migration would decrease.

Nevertheless, as we have seen, migration takes place. Government policies, individual preferences, and other factors are constantly changing, and incentives seem to change enough each year to allow more than 2 percent of US households to move to another state.

A closer look at high earners

Haushalte mit einem Einkommen von mehr als 200.000 US-Dollar machten 2016 5 Prozent aller zwischenstaatlichen Umzugsunternehmen aus, aber sie machten 36 Prozent des Einkommens aller zwischenstaatlichen Umzugsunternehmen aus.

Das Steuergesetz von 2017 hat die Migrationsanreize für diese Gruppe geändert. Die große Lücke zwischen dem höchsten Einkommensteuersatz von 12,7 Prozent in New York City und dem höchsten Steuersatz von 0 Prozent in Florida wurde offen gelegt, ebenso wie die Lücke zwischen dem höchsten Steuersatz von 13,3 Prozent in Kalifornien und dem Steuersatz von 0 Prozent in Texas, Nevada und dem US-Bundesstaat Washington.46

IRS-Daten für 2016 zeigen, dass die höchsten zwischenstaatlichen Migrationsraten für Haushalte mit dem niedrigsten Einkommen gelten. Dies liegt jedoch daran, dass die meisten dieser Haushalte aus jungen und häufig alleinstehenden Personen bestehen. Wenn Sie sich die einzelnen Alterskategorien ansehen, ist die Migrationsrate für Hochverdiener viel höher als für Mittelverdiener. Beispielsweise betrug für Menschen zwischen 45 und 54 Jahren die Migrationsrate für Haushalte mit einem Einkommen zwischen 50.000 und 200.000 USD 1,4 Prozent, für Haushalte mit einem Einkommen über 200.000 USD 2,1 Prozent. Die höchsten Verdiener sind also relativ mobil.

Eine weitere wichtige Tatsache bei Hochverdienern ist, dass sie im Allgemeinen stärker auf Steuersätze reagieren als andere Personen. Empirische akademische Studien stimmen im Allgemeinen darin überein, dass Hochverdiener bei ihren Arbeits-, Unternehmer-, Investitions- und Vermeidungsaktivitäten stärker reagieren als andere Menschen.47 Wir würden daher erwarten, dass sie auf zwischenstaatliche Steuerunterschiede reagieren.

Hochverdiener sind häufig Unternehmer, und sie können ihre Unternehmen und damit verbundene Arbeitsplätze bei der Migration mit sich führen. Sehr wohlhabende Unternehmer haben sich für Florida interessiert, wo es keine Einkommens- oder Nachlasssteuer gibt, wie diese Beispiele zeigen:

- Der reichste Mensch von New Jersey, David Tepper, zog 2016 mit seinem Hedgefonds-Geschäft Appaloosa Management nach Florida. In einem einzigen Schritt verlor die Regierung von New Jersey jährlich bis zu 100 Millionen US-Dollar an Einkommenssteuern, da Tepper manchmal mehr als 1 US-Dollar verdient Einkommen von einer Milliarde pro Jahr.48 Der Staat verlor auch die hochbezahlten Arbeitsplätze, die Teppers Geschäft schafft.

- Der Unternehmer für den elektronischen Aktienhandel, Thomas Peterffy, zog 2016 von Connecticut nach Florida. Peterffys Firma Interactive Brokers ist der größte elektronische Makler und verfügt über ein Nettovermögen von rund 20 Milliarden US-Dollar.49 Steuern sollen ein Faktor für seinen Umzug gewesen sein.50

- Der Investor und Geschäftsführer C. Dean Metropoulos verließ Connecticut 2014 in Richtung Palm Beach.51 Metropoulos ist an Hostess Brands beherrschend beteiligt. Er hat ein Nettovermögen von mehr als 2 Milliarden US-Dollar, das er durch den Kauf und die Abwicklung von Dutzenden von Unternehmen verdient hat.

- Der Hedgefonds-Manager Paul Tudor Jones zog 2015 von Connecticut nach Palm Beach. Jones hat ein Nettovermögen von mehr als 4 Milliarden US-Dollar und verdient bis zu 600 Millionen US-Dollar pro Jahr.52 Connecticut verlor jährlich bis zu 30 Millionen US-Dollar an jährlichen Einkommenssteuern aus sein Umzug.

- Der Gründer des Paychex-Unternehmens für Unternehmensdienstleistungen, Thomas Golisano, zog 2009 wegen niedrigerer Steuern von New York nach Florida. Die Associated Press berichtete: „Der 67-jährige Philanthrop aus der Region Rochester kritisiert seit langem die Regierung des Bundesstaates und hohe Steuern. . . . (H) Er beschloss, seinen Wohnsitz zu ändern, nachdem der Gesetzgeber die Steuern für wohlhabende New Yorker im neuen Staatshaushalt erhöht hatte. Golisano sagt, dass der Umzug in einen Staat ohne persönliche Einkommenssteuer ihm 13.800 USD pro Tag einsparen wird. “53 Das sind 5 Millionen USD pro Jahr.

- Der Immobilieninvestor Barry Sternlicht, der die Starwood Capital Group leitet, zog 2016 von Connecticut nach Florida. Er zitierte Steuerersparnisse für seine Entscheidung und sagte: „Es gibt einen massiven Exodus aus Connecticut. . . . Ab dem 1. Juli. . . Ich bin in Florida ansässig geworden. "54 Auf die Frage, ob er wegen hoher Steuern abgereist sei, antwortete er:" Ja. "

- Edward Lampert zog 2012 mit seinem Hedgefonds ESL Investments von Connecticut nach Miami. Lampert hatte zu diesem Zeitpunkt einen Wert von rund 3 Milliarden US-Dollar. Ein Staatsvertreter und Freund von Lampert sagte: "ESLs Abreise. . . stellt den Verlust von (nicht nur) wunderbaren Menschen und Philanthropie dar, sondern auch einen großen Teil der staatlichen Steuereinnahmen. “55

Hochsteuerstaaten verlieren nicht nur die Einkommenssteuern, die von wohlhabenden Unternehmern gezahlt werden, die ausziehen, sondern manchmal auch die Einkommenssteuern, die von den Menschen gezahlt werden, die sie beschäftigen. Die Leiterin des Business Development Board von Palm Beach County sagt, dass gutes Wetter und niedrige Steuern in den letzten Jahren 60 oder 70 Private-Equity- und Hedge-Fonds-Unternehmen in ihre Stadt gezogen haben.56

Die Städte in Florida werben aggressiv um wohlhabende Einzelpersonen und deren Unternehmen aus Hochsteuerstaaten. Florida gewinnt nicht nur die anfänglichen Arbeitsplätze, die sich bewegen, sondern auch zusätzliche Arbeitsplätze, die mit dem Wachstum der umgesiedelten Unternehmen hinzugefügt werden. Und die niedrigen Steuern in Florida ziehen nicht nur US-amerikanische Finanzunternehmen an, sondern auch internationale Unternehmen, die sich sonst möglicherweise im Nordosten niedergelassen hätten.57

Jüngste Artikel deuten darauf hin, dass das neue Bundessteuergesetz den Umzug nach Florida beschleunigt. In einem Artikel des June Wall Street Journal wurde ein Immobilienexperte aus Palm Beach mit den Worten zitiert, dass es einen Boom bei wohlhabenden Käufern gibt, die nach einer Steuerresidenz suchen.58 In einer Geschichte von June Bloomberg heißt es: „Floridas langjährige Bemühungen, Wall Street-Hotshots anzulocken, sind dank einer Bestimmung im Bundessteuergesetz, die Einwohner von Hochsteuerstaaten trifft, Fuß fassen. . . . That’s because Florida doesn’t have a state income tax and its property taxes are relatively low, whereas the tri-state area has among the highest property taxes in the country. . . . ‘SALT has been the No. 1 theme when we speak with finance companies’ about relocating or opening branch offices in Miami, said Nitin Motwani, a lead developer of a $2 billion skyscraper in Miami.”59

Some entrepreneurs have moved their financial firms out of high-tax California. Hedge fund Universa Investments moved its headquarters from California to Florida in 2014. The firm’s founder, Mark Spitznagel, “cited Miami’s favorable tax policies, emerging financial sector and access to Latin American and European investors as primary reasons for the move. . . . ‘Florida’s business-friendly policies, which are so different from California’s, offer the perfect environment for us as we expand,’ he said.”60

Billionaire investor Ken Fisher moved with his investment firm Fisher Investments from California to the state of Washington in 2011. Fisher has a net worth of more than $3 billion, and his company employs more than 2,000 people. Before the move, Fisher had expressed his frustration with California’s high taxes, and he was looking for a lower-tax location not just for himself but also for his employees.61 Washington has no income tax.

As a zero-income-tax state, Tennessee is also booming. The Wall Street Journal reported in May: “AllianceBernstein Holding LP plans to relocate its headquarters, chief executive and most of its New York staff to Nashville, Tenn., in an attempt to cut costs. . . . In a memo to employees, AllianceBernstein cited lower state, city and property taxes compared with the New York metropolitan area among the reasons for the relocation. Nashville’s affordable cost of living, shorter commutes and ability to draw talent were other factors.”62 The company has about 3,400 employees, and it considered 30 different cities in its search for a new home.

Wealthy professional athletes are responsive to state tax differences. After California hiked its tax rate on millionaires in 2012, golfer Phil Mickelson said that he had to take “drastic action” because of the hike.63 Mickelson moved from California to Texas in 2014. He earns about $60 million a year, so the move would have saved him millions of dollars a year.64 In commenting on Mickelson’s tax situation, golfer Tiger Woods said he himself moved from California to Florida in the 1990s to reduce his tax burden.65

Concern exists about the effect of the 2017 tax law on professional sports.66 Even before the law, statistical research found that teams in low-tax cities outperform teams in high-tax cities because it is easier to recruit top players to the former.67 With the tax law, the United States will become a little more like Europe, where large tax differences between countries drive wealthy athletes, entertainers, and other millionaires to Switzerland.68

In their book An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of States, Arthur Laffer and coauthors present data from 1993 to 2010 suggesting that the nine states without income taxes (Alaska, Florida, Nevada, New Hampshire, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Washington, and Wyoming) are a particularly strong draw for high earners.69

Recent IRS data support that view. In 2016, 166,000 interstate migrant households had incomes of more than $200,000, and their aggregate income was $86 billion. In that group, households with income totaling $32 billion moved to the nine states without income taxes. Thus, among those high-income migrants, 37 percent of the income moved to 18 percent of the states.

In 2016, the average in-migration ratio for the nine states with no income tax was 1.13 (Table 1, column 2). But the average ratio for those states in the over $200,000 group is much higher at 1.41 (Table 2, column 3). Thus, the zero-income-tax states are a net migration draw, but they are a particularly strong draw for high earners. The one exception is Alaska.

The average income level within the over $200,000 group can indicate the presence of very high earners. In 2016, the average income of all interstate migrants in that top group was $518,000. But the averages for in-migrants to Wyoming and Florida were $897,000 and $849,000, respectively, which were by far the highest averages among the states. Wyoming and Florida do not have income taxes or estate taxes, and they draw very-high-income migrants.

Some analysts say that high earners hesitate to move out of high-tax states because that is where their business and social relationships are. But New York residents who are sick of paying high taxes can establish a new permanent residence in Florida and continue to undertake business and social activities in New York for part of the year. Generally speaking, they can spend up to 183 days in New York without being a tax resident of that state. They need to carefully document their time and activities in Florida to withstand a challenge by New York tax authorities, but that is a common tax-reduction strategy by high earners.70

When state policymakers think about the taxation of high earners, they should recognize that their states lose more than just income taxes when high earners leave. Many wealthy businesspeople are angel and venture investors. They plow their wealth back into young, growing companies, often in the region where they live. If a state loses wealthy individuals, it may also lose startup and entrepreneurial activities down the road.

The wealthy also make large contributions to health, education, and cultural charities in their states. You can see that pattern in a recent Philanthropia.com report that profiles the largest givers in each state.71 Phil Knight, cofounder of Nike in Oregon, gave $500 million to the Oregon Health and Science University. Phillip Frost, a Florida pharmaceutical billionaire, has given hundreds of millions of dollars to Miami-area health facilities, universities, and art and science museums. Jon Huntsman, founder of a chemical company, gave $175 million to the Huntsman Cancer Center in Utah. Darla Moore, a partner in the investment firm Rainwater Inc., has donated tens of millions of dollars to education and arts institutions in her state of South Carolina.

Individuals gave $280 billion to charity in 2016, and foundations gave $58 billion.72 The top 1 percent of earners make one-third of the nation’s charitable contributions.73 The wealthiest 1.4 percent of Americans give 86 percent of all charitable donations made at death.74 If high-tax states lose wealthy individuals to lower-tax states, they will likely lose a share of their state’s philanthropy.

A New Jersey report prompted by the possible loss of charitable giving because of taxpayer flight noted: “Wealthy households contribute disproportionately more to charitable causes both from their household assets and from their foundations, trusts, and donor advised funds. Our analysis indicates that in recent years wealth has been leaving New Jersey in larger amounts than wealth has been entering the state due to household migration.”75

In sum, the wealthy are important to the states they reside in for many reasons. They pay a large share of state income taxes; they run businesses and create jobs; they invest in growth companies; and they engage in philanthropy. Time will tell how large the migration effect will be from the 2017 tax law. But even a modest increase in moves by top earners could be a substantial blow to high-tax states.

A Closer Look at Retirees

People age 65 and older accounted for 10 percent of interstate movers and 13 percent of the income of movers in 2016. States are increasingly putting out a welcome mat for this group by reducing taxes on retirement income and estates. The thinking is that seniors have substantial wealth to spend and they impose little cost on governments for services such as public schools.

Of the 41 states that impose broad-based income taxes, 36 provide special breaks for pension income.76 A few states offer full exemptions, but most have partial exemptions with a dollar cap. More states offer breaks for public pension income than for private pension income. But Illinois, for example, exempts nearly all public and private pension income, including income from 401(k) plans.77 The National Conference of State Legislatures says that states use such breaks as “an economic development tool by attracting retired people to, or retaining them in, a state.”78

Nearly all the states with an income tax used it to fully tax pension income. But beginning in the 1970s, states began adopting pension tax exemptions, often in regional patterns. They adopted them when neighboring states did so as a “weapon of policy competition,” said Karen Smith Conway and Jonathan Rork.79 Over time, exemption amounts have increased as states have raised the competitive bar to attract retirees.

A parallel trend has been the reduction of estate and inheritance taxes, as states have competed to attract wealthy retirees. All 50 states used to impose one or both of those “death taxes,” but today just 17 states and the District of Columbia do so.80 The remaining death-tax states are in the Northeast (Connecticut, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and Vermont), the Northwest (Oregon and Washington), and the Midwest (Illinois, Iowa, Minnesota, and Nebraska). Kentucky and Hawaii also impose them.

Before 2005, the federal government provided individuals a credit against state death taxes up to a fixed amount, so it made sense for states to adopt a death tax up to that level. In earlier decades, many states imposed excess death taxes beyond the federal credit amount. In the 1960s, many states imposed taxes on estates of as little as $10,000.81 But since the 1970s, a competitive trend for states has been to reduce these excess death taxes.82

Then in 2005, the repeal of the federal credit accelerated the downsizing of death taxes. Since then, competition to attract wealthy retirees has prompted most states to completely repeal these taxes.83 Many of the states that have retained them have increased the exemption amounts.

Clearly, state policymakers believe that retirees are responsive to tax differences. Retirees are often footloose, and they can consult sources such as Kiplinger’s “10 Most Tax-Friendly States for Retirees, 2017” and SmartAsset’s “Most Tax Friendly Places for Retirees.”84 The latter is an interactive site with detailed tax information down to the county level, and it provides a “retirement tax friendliness index” for each location.

On its website, AARP discusses “Which States Provide the Best Tax Breaks for Retirees?”85 The organization is a vigorous lobbyist for reducing state taxes on retirement income, and it informs its 38 million members about state tax differences.86

Do taxes influence interstate moves by seniors? Statistical studies generally find that they do, but the results are mixed.

A 1992 study by David Clark and William Hunter finds that high inheritance and estate taxes deterred state in-migration.87 A 2004 study by Jon Bakija and Joel Slemrod finds that “high state inheritance and estate taxes and sales taxes have statistically significant, but modest, negative impacts on the number of federal estate tax returns filed in a state.”88 In 2001 and 2003 studies, Karen Smith Conway and Andrew Houtenville find that low income, property, and death taxes attract elderly migration.89 But in 2006 and 2012 studies, Smith Conway and Jonathan Rork find that death taxes and pension tax breaks have little, if any, effect on migration.90

However, the simple patterns of senior migration suggest that taxes do influence location decisions. Consider Kiplinger’s “State-by-State Guide to Taxes on Retirees,” which classifies each state as “most tax-friendly,” “tax-friendly,” “mixed,” “not tax-friendly,” and “least tax-friendly.”91 The classification considers income taxes, sales taxes, property taxes, motor vehicle taxes, and taxes on pension income and Social Security benefits.

Those categories can be compared with the elderly migration ratios in column 1 of Table 2. For the 20 states that are “most tax-friendly” or “tax-friendly,” the average ratio is 1.11, meaning net in-migration. For the 20 “not” and “least” tax-friendly, the ratio is 0.90, meaning net out-migration. Thus, seniors are gravitating toward states that have the best retirement tax climates.

To get an idea of where the very wealthiest retirees are moving, we can look at federal estate tax returns. In 2016, federal estate taxes were potentially payable above exemption amounts of $5.45 million for singles and $10.9 million for married couples. Florida has 6 percent of the U.S. population, but its residents paid 17 percent of federal estate taxes in 2016.92 That figure is up from 12 percent 20 years ago. Meanwhile, the estate tax share in four high-tax northeastern states has fallen, as more of the wealthiest elderly Americans are living elsewhere.93

What Should States Do?

The passage of the 2017 federal tax law has heightened tax competition between the states. The capping of federal deductibility has increased the state and local tax bite on millions of households in high-tax states. At the same time, today people can easily find information to compare state tax burdens.

Some analysts say that people are migrating from northern states to southern states for the warmer climate, not lower taxes.94 Yet, as noted, only 2 percent of interstate movers say climate is the main reason for their move. The next few years under the new tax law should give us a clearer view.

More importantly, policymakers in northern states cannot do anything about the warm and sunny climate in southern states. But they can do something about taxes, housing costs, school quality, and other standard-of-living factors affected by government policy. By providing government services more efficiently at lower cost, states can both attract in-migrants and benefit current residents alike.

To grow, states need in-migrants of all types, not just retirees and the wealthy. Urban economist Edward Glaeser argues that attracting younger, educated people with modest incomes is perhaps more important than attracting older, wealthier people.95 He says that cities with young and brainy populations are best able to generate growth in our dynamic economy.

To attract all types of people and investment, states should create simple, neutral, low-rate tax codes. They should reduce regulations that dissuade entrepreneurship, and they should pursue land-use reforms to keep housing prices down.96 States should also inject more competition into public schooling to improve quality and attract families.

State policymakers should focus on increasing individual freedom. The Cato Institute publishes Freedom in the 50 States, which scores the states on 175 variables covering fiscal, regulatory, and personal freedom.97 The variables generally measure the ability of individuals to act without government restraint.

In the 2016 edition of the report, William Ruger and Jason Sorens find that interstate migration flows are strongly correlated with state freedom scores after controlling for climate, the cost of living, and other factors. Numerous studies have confirmed a link between economic freedom and interstate migration.98 Americans are gravitating toward states offering greater individual freedom.

Those results are not surprising. Historically, the United States has been a huge draw for international migrants seeking economic and personal freedom. Freedom is a migration draw not just because it has intrinsic value but also because it fosters innovation and growth, which in turn attracts businesses, entrepreneurs, and job seekers.

Some U.S. states have been losing people from out-migration for decades. The new federal tax law should be a wake-up call for such laggard states to improve their tax codes, slim down their governments, and allow residents more economic and personal freedom.

Remarks

1. Frank Sammartino, Philip Stallworth, and David Weiner, “The Effect of the TCJA Individual Income Tax Provisions across Income Groups and across the States,” Tax Policy Center, March 28, 2018.

2. Frank Sammartino, Philip Stallworth, and David Weiner, “The Effect of the TCJA Individual Income Tax Provisions across Income Groups and across the States,” Tax Policy Center, March 28, 2018.

3. Joint Committee on Taxation, “Tables Related to the Federal Tax System as in Effect 2017 through 2026,” JCX-32R-18, April 24, 2018, Table 7.

4. However, SALT deductions were limited for taxpayers subject to the alternative minimum tax and those subject to the “Pease” limitation on itemized deductions.

5. Joint Committee on Taxation, “The Taxation of Individuals and Families,” JCX-41-17, September 12, 2017, Tables 2 and A-1.

6. Kirk J. Stark, “Fiscal Federalism and Tax Progressivity: Should the Federal Income Tax Encourage State and Local Redistribution?,” University of California Law Review 51, no. 1 (2004): 1418.

7. Congressional Budget Office, “The Deductibility of State and Local Taxes,” February 2008, p. 7th

8. Joint Committee on Taxation, “Tables Related to the Federal Tax System as in Effect 2017 through 2026,” JCX-32R-18, April 24, 2018, Table 7.

9. State of California, Franchise Tax Board, “Preliminary Report on Specific Provisions of the Federal Tax Cuts and Jobs Act,” March 20, 2018, Table 3.

10. Ronald Reagan, “Remarks and a Question-and-Answer Session with Economic Editors during a White House Briefing on Tax Reform,” June 7, 1985,http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/index.php?pid=38740.

11. Joint Committee on Taxation, “Tables Related to the Federal Tax System as in Effect 2017 through 2026,” JCX-32R-18, April 24, 2018, Table 7.

12. Jared Walczak, “The State and Local Tax Deduction: A Primer,” Tax Foundation, March 2017.

13. State of New Jersey, Department of Treasury, “Statistics of Income,” January 12, 2018, Tables B and 3.1b. Also see New York State, Department of Taxation and Finance, “Analysis of 2014 Personal Income Tax Returns,” Table 21. New York data are for 2014; New Jersey data are for 2015.

14. Justin Garosi and Jason Sisney, “Top 1 Percent Pays Half of State Income Taxes,” California Legislative Analyst’s Office, December 4, 2014.

15. Jeff Stein, “N.J. Backs Down on Millionaire’s Tax,” Washington Post, May 29, 2018.

16. IRS migration data are at https://www.irs.gov/statistics/soi-tax-stats-migration-data. And see Kevin Pierce, “SOI Migration Data: A New Approach,” Statistics of Income Bulletin, Internal Revenue Service, Summer 2015.

17. The IRS data include the number of tax exemptions, which measures the number of people in each household or tax filing unit.

18. Raven Molloy, Christopher L. Smith, and Abigail Wozniak, “Internal Migration in the United States,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 25, no. 2 (Spring 2011): 173–96.

19. Raven Molloy, Christopher L. Smith, and Abigail Wozniak, “Internal Migration in the United States,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 25, no. 2 (Spring 2011): 173–96. And see Greg Kaplan and Sam Schulhofer-Wohl, “Understanding the Long-Run Decline in Interstate Migration,” Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, October 2015.

20. U.S. Census Bureau, “CPS Historical Migration/Geographic Mobility Tables,” Table A-1. The Census Bureau reported that 1.7 percent of Americans moved between states in 2017.

21. Arthur B. Laffer et al., An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of States (New York: Wiley, 2014), Table 2.7. See also Tax Foundation, “State to State Migration Data,” https://interactive.taxfoundation.org/migration.

22. The website www.howmoneywalks.com maps the IRS AGI data for the period from 1993 to 2016.

23. U.S. Census Bureau, “CPS Historical Migration/Geographic Mobility Tables,” Table A-5.

24. Taylor Tepper, “These Are the Best and Worst States for Retirement,” Bankrate.com, July 12, 2018.

25. Tabulation from the U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Survey, Annual Social and Economic Supplement, 2017, https://cps.ipums.org/cps/index.shtml.

26. U.S. Census Bureau, “State and Local Government Finance,” https://www.census.gov/govs/local/.

27. Karlyn Bowman, “Public Opinion on Taxes: 1937 to Today,” American Enterprise Institute, April 2016.

28. The state tax ratios for 2015 are Alabama (7.2 percent), Alaska (4.9 percent), Arizona (8.2 percent), Arkansas (9.0 percent), California (9.6 percent), Colorado (8.1 percent), Connecticut (10.2 percent), Delaware (5.7 percent), District of Columbia (11.8 percent), Florida (6.6 percent), Georgia (8.1 percent), Hawaii (11.6 percent), Idaho (7.9 percent), Illinois (10.1 percent), Indiana (8.6 percent), Iowa (9.3 percent), Kansas (8.5 percent), Kentucky (8.8 percent), Louisiana (8.4 percent), Maine (11.0 percent), Maryland (9.5 percent), Massachusetts (9.0 percent), Michigan (8.5 percent), Minnesota (10.4 percent), Mississippi (9.3 percent), Missouri (7.9 percent), Montana (7.6 percent), Nebraska (9.2 percent), Nevada (8.2 percent), New Hampshire (7.1 percent), New Jersey (10.0 percent), New Mexico (8.9 percent), New York (13.0 percent), North Carolina (8.3 percent), North Dakota (8.7 percent), Ohio (9.5 percent), Oklahoma (7.2 percent), Oregon (8.4 percent), Pennsylvania (8.7 percent), Rhode Island (10.2 percent), South Carolina (7.9 percent), South Dakota (7.2 percent), Tennessee (6.5 percent), Texas (8.2 percent), Utah (8.4 percent), Vermont (10.9 percent), Virginia (7.8 percent), Washington (8.1 percent), West Virginia (9.4 percent), Wisconsin (9.3 percent), Wyoming (8.0 percent).

29. State-to-state flows are available on the IRS “U.S. Population Migration Data” webpage, https://www.irs.gov/statistics/soi-tax-stats-migration-data.

30. Detailed data by age are available on the IRS “U.S. Population Migration Data” webpage, https://www.irs.gov/statistics/soi-tax-stats-migration-data. The age is the age of the primary taxpayer, which the IRS derives by matching Social Security numbers on tax returns to data from the Social Security Administration.

31. Government of the District of Columbia, “Tax Rates and Tax Burdens in the District of Columbia: A Nationwide Comparison, 2016,” December 2017.

32. Note that Bridgeport and Newark have extraordinarily high property taxes, and that some of the other high-tax cities, such as Detroit and Philadelphia, impose city income taxes on top of state income taxes.

33. “Best States to Move to in 2018 for Lower Taxes,” Kiplinger.com, November 21, 2017. See also Sandra Block and David Muhlbaum, “The 10 Most Tax-Friendly States in the U.S.,” Kiplinger.com, October 4, 2017.

34. Adam McCann, “2018’s Tax Burden by State,” WalletHub, April 9, 2018.

35. Laffer et al., An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of States (New York: Wiley, 2014), pp. 229–43. The authors look at the relationship between state and local taxes, spending, and quality of services for schools, police, corrections, highways, and other services. They find, for example, that taxpayers in higher-tax California get less bang for their buck than taxpayers in lower-tax Texas. One reason is the excess compensation of employees in California government. Another reason is the excess regulation in California, which, for example, results in a mile of highway costing twice as much to build as in Texas.

36. Jeff Daniels, “Californians Fed Up with Housing Costs and Taxes Are Fleeing State in Big Numbers,” CNBC.com, March 20, 2018.

37. American Automobile Association, “Gas Prices,” https://gasprices.aaa.com.

38. Richard J. Cebula, “Migration and the Tiebout-Tullock Hypothesis Revisited,” Review of Regional Studies 32 (2002): 87–96; Richard J. Cebula and Usha Nair-Reichert, “Migration and Public Policies: A Further Empirical Analysis,” Journal of Economics and Finance 36, no. 1 (2012): 238–48; Richard J. Cebula, Usha Nair-Reichert, and Christopher K. Coombs, “Total State In-Migration Rates and Public Policy in the United States,” Regional Studies, Regional Science 1, no. 1 (2014): 101–15; Richard J. Cebula and Gigi M. Alexander, “Determinants of Net Interstate Migration, 2000–2004,” Journal of Regional Analysis and Policy 36, no. 2 (2006): 116–23; Richard J. Cebula, “The Impacts of State Government Tax and Spending Policies on Domestic Migration in the United States,” Journal of Economics 42, no. 2 (2016): 1–22.

39. Richard J. Cebula and Usha Nair-Reichert, “Migration and Public Policies: A Further Empirical Analysis,” Journal of Economics and Finance 36, no. 1 (2012): 238–48.

40. The Tiebout hypothesis is named for Charles Tiebout. See Charles Tiebout, “A Pure Theory of Local Expenditures,” Journal of Political Economy 64 (1956): 416–24.

41. Yu Hsing, “A Note on Interstate Migration and Tax Burdens: New Evidence,” Journal of Applied Business Research 12 (Winter 1995/1996): 12–14; Karen Smith Conway and Andrew J. Houtenville, “Elderly Migration and State Fiscal Policy: Evidence from the 1990 Census Migration Flows,” National Tax Journal 54 (March 2001): 103–23; Karen Smith Conway and Andrew J. Houtenville, “Out with the Old, In with the Old: A Closer Look at Younger versus Older Elderly Migration,” Social Science Quarterly 84 (May 2003): 309–28; Mark Gius, “The Effect of Income Taxes on Interstate Migration: An Analysis by Age and Race,” Annals of Regional Science 46 (February 2011): 205–18; David E. Clark and William J. Hunter, “The Impact of Economic Opportunity, Amenities and Fiscal Factors on Age-Specific Migration Rates,” Journal of Regional Science 32 (August 1992): 349–65; Robert R. Preuhs, “State Policy Components of Interstate Migration in the United States,” Political Research Quarterly 52 (September 1999): 527–47; Roger Cohen, Andrew Lai, and Charles Steindel, “Tax Flight Has Tangible Effects on Income Tax Revenue,” State Tax Notes, February 20, 2012; Antony Davies and John Pulito, “Tax Rates and Migration,” Mercatus Center at George Mason University, August 2011.

42. Roger S. Cohen, Andrew E. Lai, and Charles Steindel, “A Replication of ‘Millionaire Migration and State Taxation of Top Incomes,’” Public Finance Review 43, no. 2 (2015): 206–25.

43. Assuming that the taxpayer was in the top federal bracket of 39.6 percent, the effective rate prior to 2018 was 5.42 percent (8.97–8.97*0.396).

44. Cristobal Young and Charles Varner, “Millionaire Migration and State Taxation of Top Incomes,” National Tax Journal 64 (2011): 255–84; Cristobal Young et al., “Millionaire Migration and Taxation of the Elite,” American Sociological Review 81, no. 3 (2016): 421–66; Charles Varner, Cristobal Young, and Allen Prohofsky, “Millionaire Migration in California: Administrative Data for Three Waves of Tax Reform,” Stanford Center on Poverty and Inequality, July 2018. Young and Varner’s studies are critiqued in Antony Davies and John Pulito, “Tax Rates and Migration,” Mercatus Center at George Mason University, August 2011.

45. Sally Wallace, “The Effect of State Income Tax Structure on Interstate Migration,” Georgia State University, Fiscal Research Program, December 2002. See also Martin Feldstein and Marian Vaillant Wrobel, “Can State Taxes Redistribute Income?” Journal of Public Economics 68, no. 3 (1994): 369–96; and Seth H. Giertz and Mehmet S. Tosun, “Migration Elasticities, Fiscal Federalism, and the Ability of States to Redistribute Income,” National Tax Journal 65, no. 4 (December 2012): 1069–92.

46. New York City’s top rate is 3.876 percent, which is on top of New York State’s top rate of 8.82 percent.

47. For example, see Emmanuel Saez, Joel Slemrod, and Seth H. Giertz, “The Elasticity of Taxable Income with Respect to Marginal Tax Rates: A Critical Review,” Journal of Economic Literature 50, no. 1 (2012): 3–50; Martin Feldstein, “The Effect of Marginal Tax Rates on Taxable Income: A Panel Study of the 1986 Tax Reform Act,” Journal of Political Economy 103, no. 3 (1995): 551–72; Robert Carroll et al., “Entrepreneurs, Income Taxes, and Investment,” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper no. 6374, January 1998; Jonathan Gruber and Emmanuel Saez, “The Elasticity of Taxable Income: Evidence and Implications,” Journal of Public Economics 84, no. 1 (2002): 1–32; Gerald Auten and David Joulfaian, “The Taxable Income Elasticity of High-Income Taxpayers: Evidence from a Long Panel,” May 2009; Robert Carroll, “Do Taxpayers Really Respond to Changes in Tax Rates,” Working Paper no. 78, U.S. Treasury, Office of Tax Analysis, November 1998; Bradley Heim, “The Effect of Recent Tax Changes on Taxable Income: Evidence from a New Panel of Tax Returns,” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 9, no. 1 (2009): 147–63; and Aspen Gorry, R. Glenn Hubbard, and Aparna Mathur, “The Elasticity of Taxable Income in the Presence of Intertemporal Income Shifting,” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper no. 24531, April 2018. A number of studies on the responsiveness of high earners are summarized in Alan Reynolds, “Of Course 70% Tax Rates Are Counterproductive,” Wall Street Journal, May 7, 2012.

48. Robert Frank, “Billionaire to Save Hundreds of Millions from Florida Move,” CNBC.com, April 6, 2016. See also Robert Frank, “One Top Taxpayer Moved, and New Jersey Shuddered,” New York Times, April 30, 2016.

49. Rob Wile, “Meet the Richest Man in Florida, a Hungarian Immigrant Who Hates Socialism and Hangs Out at Mar-a-Lago,” Time, October 6, 2017.

50. Dan Haar, “Two Billionaires Head for Florida, Deepening CT’s Cash Crisis,” Hartford Courant, March 3, 2016.

51. Dan Haar, “Two Billionaires Head for Florida, Deepening CT’s Cash Crisis,” Hartford Courant, March 3, 2016.

52. Marc E. Fitch, “Connecticut Billionaire Moves to Florida; Could Add $30 Million to the Deficit,” Yankee Institute, June 30, 2016.

53. Mike Groll, “Rochester Billionaire Tom Golisano Changes Address to Florida to Avoid New York Taxes,” Syracuse.com, May 15, 2009.

54. Svea Herbst-Bayliss and Lawrence Delevingne, “More Investors Leaving U.S. Northeast for Florida: Sternlicht,” Reuters.com, September 13, 2016.

55. Neil Vigdor, “Lampert Folds Up Tent in Greenwich, Moves Hedge Fund to Florida,” Greenwich Time, June 6, 2012.

56. Dan Weil, “Hedge Funds Flock to Palm Beach and WPB, Boosting Office Market,” Real Deal, May 18, 2016.

57. Nicholas Nehamas, “Miami Banks on Future as a Financial Hub,” Miami Herald, February 16, 2015.

58. Robyn A. Friedman, “Tax Laws Have Buyers on the Move,” Wall Street Journal, June 8, 2018.

59. Lynnley Browning and Gillian Tan, “Fund Managers Are Ditching Wall Street for Florida,” Bloomberg, June 4, 2018.

60. Nancy Dahlberg, “California Hedge Fund Universa Moving Its Base to Miami,” Miami Herald, February 9, 2014.

61. Brooke Southall, “The World’s Largest RIA Takes the Cult-on-the-Hill to the Washington State Woods,” RIAbiz, August 19, 2009.

62. Sarah Krouse, “Large New York Money Manager Alliance Bernstein Is Moving to Nashville,” Wall Street Journal, May 1, 2018.

63. “Mickelson Vows ‘Drastic Changes,’” Foxsports.com, January 20, 2013.

64. Stephen Frank, “Is Phil Mickelson Finally Abandoning California for Income Tax-Free Florida?,” capoliticalreview.com, November 11, 2014.

65. “Tiger Woods Admits He Left California Because of High Tax Rates after Rival Phil Mickelson Apologizes for Saying He May Quit West Coast,” DailyMail.com, January 23, 2013.

66. Ronald Blum, “Florida, Texas May Attract Athletes after Tax Law Change,” U.S. News and World Report, December 22, 2017.

67. Erik Hembre, “Income Taxes and Team Performance: Do They Matter?” September 28, 2017, http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2946169. See also Max Ehrenfreund, “Study: Blue-State Politicians Are Undermining Their Home-State Sports Teams,” Washington Post, April 24, 2017.

68. Chris Edwards and Daniel J. Mitchell, Global Tax Revolution (Washington: Cato Institute, 2008), chap. 5.

69. Laffer et al., An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of States (New York: Wiley, 2014).

70. James Stewart discusses New York audits and the large efforts people put into avoiding New York taxes in James B. Stewart, “Tax Me if You Can,” New Yorker, March 19, 2012, pp. 16–23.

71. Maria Di Mento, “From Alaska to Florida: The Biggest Living Donors in Every State, Philanthropy.com, June 20, 2017.

72. National Philanthropic Trust, “Charitable Giving Statistics,” www.nptrust.org/philanthropic-resources/charitable-giving-statistics.

73. Almanac of American Philanthropy, “Who Gives Most to Charity,”www.philanthropyroundtable.org/almanac/statistics/who-gives.

74. Almanac of American Philanthropy, “Who Gives Most to Charity,”https://www.philanthropyroundtable.org/almanac/statistics/who-gives.

75. John Havens, “Migration of Wealth in New Jersey and the Impact on Wealth and Philanthropy,” Center on Wealth and Philanthropy, Boston College, January 22, 2010, p. 13.

76. National Conference of State Legislatures, “State Personal Income Taxes on Pensions and Retirement Income: Tax Year 2014,” April 3, 2015.

77. Jake Griffin, “How Not Taxing Retirees’ Income Costs Illinois,” Dailyherald.com, August 2, 2017.

78. National Conference of State Legislatures, “State Personal Income Taxes on Pensions and Retirement Income: Tax Year 2014,” April 3, 2015, p. 1.

79. Karen Smith Conway and Jonathan C. Rork, “The Genesis of Senior Income Tax Breaks,” National Tax Journal 65, no. 4 (December 2012): 1056.

80. Jared Walczak, “State Inheritance and Estate Taxes: Rates, Economic Implications, and the Return of Interstate Competition,” Tax Foundation, July 17, 2017.

81. Karen Smith Conway and Jonathan C. Rork, “State Death Taxes and Elderly Migration—The Chicken or the Egg?,” National Tax Journal 59, no. 1 (March 2006): 97–128.

82. Jon Bakija and Joel Slemrod, “Do the Rich Flee from High State Taxes? Evidence from Federal Estate Tax Returns,” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper no. 10645, July 2004.

83. Laura Sanders, “Why More States Are Killing Estate Taxes,” Wall Street Journal, June 16, 2017.

84. Sandra Block, “10 Most Tax-Friendly States for Retirees, 2017,” slide show, Kiplinger, November 15, 2017, https://www.kiplinger.com/slideshow/retirement/T006-S001-most-friendly-states-for-retirees-taxes/index.html. See also “Most Tax Friendly Places for Retirees,” SmartAsset, https://smartasset.com/retirement/retirement-taxes.

85. Patrick Kiger, “Which States Provide the Best Tax Breaks for Retirees?” aarp.org, June 5, 2017. See also Carole Fleck, “Tax-Friendly States,” aarp.org, June 2015.

86. Christina Hernandez Sherwood, “A Tax Break on Retiree Income,” AARP, March 1, 2017, https://states.aarp.org/nj-taxes.

87. David E. Clark and William J. Hunter, “The Impact of Economic Opportunity, Amenities and Fiscal Factors on Age-Specific Migration Rates,” Journal of Regional Science 32 (August 1992), 349–65.

88. Jon Bakija and Joel Slemrod, “Do the Rich Flee from High State Taxes? Evidence from Federal Estate Tax Returns,” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper no. 10645, July 2004.

89. Karen Smith Conway and Andrew J. Houtenville, “Elderly Migration and State Fiscal Policy: Evidence from the 1990 Census Migration Flows,” National Tax Journal 54 (March 2001): 103–23. See also Karen Smith Conway and Andrew J. Houtenville, “Out with the Old, In with the Old: A Closer Look at Younger versus Older Elderly Migration,” Social Science Quarterly 84 (May 2003): 309–28.

90. Karen Smith Conway and Jonathan C. Rork, “No Country for Old Men (or Women)—Do State Tax Policies Drive Away the Elderly?,” National Tax Journal 65, no. 2 (June 2012): 313–56. See also Karen Smith Conway and Jonathan Rork, “State Death Taxes and Elderly Migration—The Chicken or the Egg?,” National Tax Journal 59, no. 1 (March 2006): 97–128.

91. “State-by-State Guide to Taxes on Retirees,” Kiplinger, November 2017.

92. Internal Revenue Service, “Table 2. Estate Tax Returns Filed in 2016, Deductions, by State of Residence,”http://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-soi/16es02st.xls.

93. Greg Sullivan, “Eight Reasons to Question Professor Cristobal Young’s Conclusions about Millionaire Migration,” Pioneer Institute, May 2018, p. 10.

94. Michael Mazerov, “State Taxes Have a Negligible Impact on Americans’ Interstate Moves,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, May 21, 2014.

95. Edward Glaeser, Triumph of the City (New York: Penguin, 2012).

96. Vanessa Brown Calder, “Zoning, Land-Use Planning, and Housing Affordability,” Cato Institute Policy Analysis no. 823, October 18, 2017.

97. William P. Ruger and Jason Sorens, Freedom in the 50 States (Washington: Cato Institute, 2016). And see Cato Institute’s website www.freedominthe50states.org.

98. Nathan Ashby, “Economic Freedom and Migration between U.S. States,” Southern Economic Journal 73, no. 3 (2007): 677–97; Richard J. Cebula and J. R. Clark, “Migration, Economic Freedom, and Personal Freedom: An Empirical Analysis,” Journal of Private Enterprise 27 (Fall 2011): 43–62; Richard J. Cebula, “The Impact of Economic Freedom and Personal Freedom on Net In-Migration in the U.S.: A State-Level Empirical Analysis, 2000 to 2010,” Journal of Labor Research 35 (March 2014): 88–103; J. Matthew Shumway and James A. Davis, “Economic Freedom, Migration, and Income Change in the United States: 1995 to 2010,” Professional Geographer 68, no. 3 (2016): 390–98; J. Matthew Shumway, “Economic Freedom, Migration and Income Change among U.S. Metropolitan Areas,” Current Urban Studies 6, no. 1 (2018): 1–20.