The White House and Republican lawmakers made great promises when they passed a comprehensive tax bill in President Donald Trump's first year in office that would boost the economy and make the tax bill simpler and fairer.

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017, passed with only Republican votes, became the Trump administration's major legislative achievement. Tax rates for individuals and companies were lowered, new incentives were created, the standard withholding and inheritance tax exemptions were increased, and the US was moving towards a territorial tax system.

Republicans in Congress have touted the law's success, while Democrats have attacked it as a giveaway for the rich and corporate.

In the waning days of the Trump administration, Bloomberg Tax examined the stated goals of the law and looked at which of its top seven promises were fulfilled.

"The most prominent claims were often the least serious," said Matt Gardner, a senior fellow at the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy.

Promise: A simpler tax number

Some aspects of the law have made filing tax returns easier.

For individuals, the law increased the standard deduction, which allowed millions of people not to list their annual tax returns. In addition, the threshold for a parallel taxation system aimed at individuals receiving an oversized amount of credits and deductions known as the alternative minimum tax and a similar system for businesses has been removed.

But other changes to the tax law – like a 20% write-off for pass-through business owners and the Byzantine international provisions of the law – were far from easy even before the IRS penned hundreds of pages of compliance regulations for you.

Beyond the Code, Republicans promised that people could pay their taxes on a postcard-sized form.

House Speaker at the time, Paul Ryan, shows off a counterfeit tax form the size of a postcard before the law is passed. The IRS abandoned a modified version of the postcard after a year.

Photographer: Andrew Harrer / Bloomberg

That was in some ways true in 2018 when the IRS downsized Form 1040 from two full pages to a small one-page document. For this year, however, the lines for reporting income, credits and deductions have been moved to six separate attached annexes.

Then, in 2019, the IRS reverted to a two-page 1040 form, and the agency reduced the number of schedules to three – somewhat soothing accountants who complained that the previous year's "postcard" was a mess.

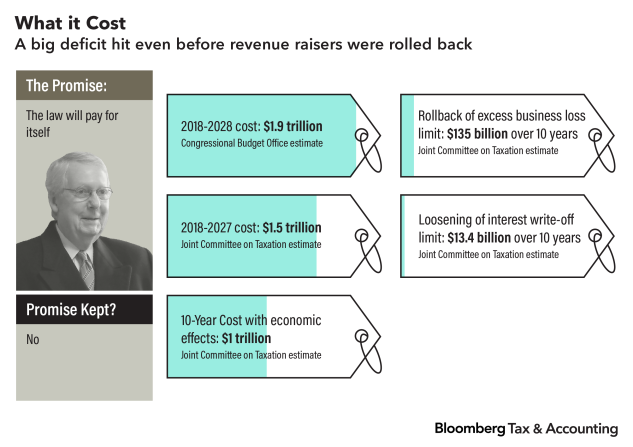

Promise: Pay for yourself

After the bill was passed, Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin began arguing that the resulting economic growth would generate enough tax revenue to amortize the tax code revision.

“At the time, economists didn't think this was true in any way, and it is definitely not true,” said Eric Ohrn, assistant professor of economics at Grinnell College.

The claim has since been widely ridiculed, as the Congressional Budget Office estimates the law paid about a fifth itself.

The tax bill revision was originally estimated at just under $ 1.5 trillion over a decade. That 10-year window, as well as temporary provisions like the reduced single rates, have effectively masked the real cost of the law, some tax experts claim.

Provisions, which increase revenue by restricting companies' ability to write off things like losses and borrowing interest, have effectively pushed those benefits beyond that 10-year window by allowing companies to make unused deductions indefinitely in the future Postponing years, noted Steve Rosenthal, a senior fellow at the Center for Tax Policy.

Last March, lawmakers cut back some of these revenue streams to cushion the economic blow from the pandemic.

"The TCJA was actually more expensive than it looked," said Rosenthal. “Because the revenue was a gimmick of timing. And then these timing gimmicks were reversed under the Covid legislation. "

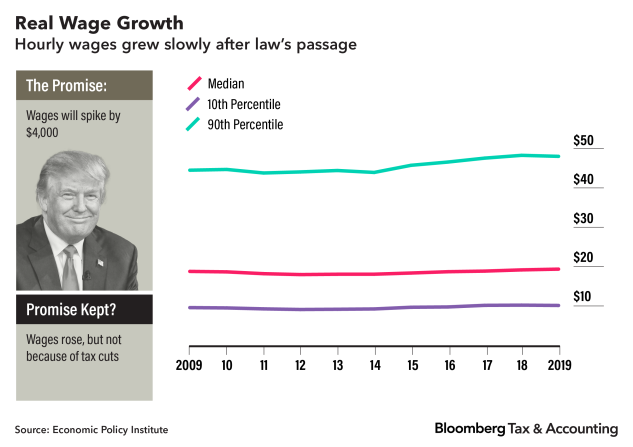

Promise: rising wages

Trump and his economic advisors claimed the tax bill would quickly earn the average family an additional $ 4,000 in wages.

In the weeks after the law was passed, Verizon, Disney, Walmart, and dozens of other companies announced one-time employee bonuses. Those benefits turned out to be relatively minor, said Jane Gravelle, a senior economic policy specialist with the Congressional Research Service.

"Nobody wanted to give people higher wages just because they were getting a tax cut," she said. "In general, economists would not expect a reduction in investment taxes to have an immediate impact on wages."

In theory, the parts of the law that stimulated investment should encourage companies to invest in more plant, machinery and equipment, which would increase worker productivity and potentially encourage companies to hire more workers. Higher productivity should lead to higher pay.

The rate of wage growth has been hotly debated in recent years and depends on how you measure it, but economists agree that the law has not resulted in an increase in wages.

Although some say the trickle-down effect lasts longer and is difficult to measure over just a few years, economists attribute small wage increases in the lead up to the Covid-19 pandemic to a labor market shortage during the late-growth phase of the year Business cycle.

"I think lawmakers wanted more investment and wages, which is more of a longer-term process," said Kyle Pomerleau, resident fellow at the American Enterprise Institute. "But I don't think there is enough data or time to really judge that."

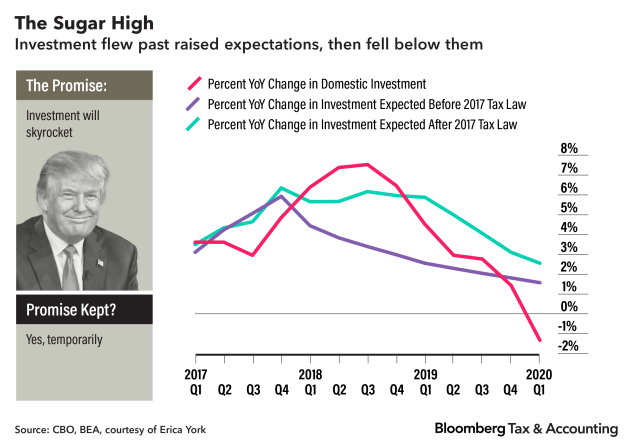

Promise: New investment

The most popular descriptor of the 2017 Tax Act impact by economists and analysts is a "sugar high". When it comes to investing, that's exactly what happened.

The lowering of the corporate tax rate and the ability to fully and instantly write off the cost of equipment and other expenses left businesses with more money to buy things and effectively made those purchases less costly.

Domestic investment in non-residential buildings skyrocketed in 2018 – even beyond the increased expectations of the CBO after the law came into force.

While the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act likely contributed to that boost, it was not enough to save investment from Trump's trade war. In 2018, his government began imposing tariffs on Chinese imports valued at hundreds of billions of dollars, prompting Beijing to retaliate with its own taxes on American goods.

“If you look at the actual investment path versus the pre- and post-TCJA projections, the investment will exceed these two projected amounts for a short time after the TCJA was signed,” said Erica York, an economist at the Tax Foundation.

The investment declines, she noted, "fit pretty well with the timing of the various tariffs that went into effect or when Trump announced that other tariffs would be considered".

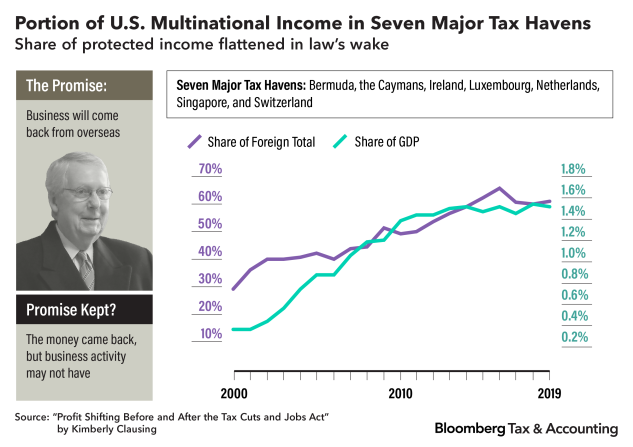

Promise: business is coming back

The law made it cheaper to repatriate profits from abroad, while at the same time preventing companies from permanently avoiding taxes on those profits by viewing them as "repatriated". Cash and other liquid assets held by offshore companies of multinational corporations were taxed at 15.5% and other assets held abroad were taxed at 8%. Ordinarily, upon repatriation to the US, these profits would be subject to corporation tax, which at the time was 35%

The impact on foreign investment by US companies is clear: from 2018, repatriated dividends skyrocketed.

Tax experts studying the ramifications of the law's international controls say there haven't been many prominent reversals in recent years – where U.S. companies are restructuring to be owned by a foreign parent company.

But companies can still be taxed on international profits below the 21% domestic rate, and the law didn't create the fully territorial tax system that Republicans were aiming for, tax experts said. The law and IRS rules for portions of international regulations also provide some competing incentives that both encourage and discourage asset building overseas.

"The whole thing was ill-structured if the incentive here was to move assets back to the US or create jobs instead of just moving cash back," said Reuven Avi-Yonah, professor at the University of Michigan Law School and Director of his International Tax LLM Program.

According to Kimberly Clausing, professor of economics at Reed College.

The law "really improves the problem with one hand and makes it worse with the other, and the two effects cancel each other out," said Clausing, who advised the Biden campaign and previously studied corporate profit shifting after the 2017 Tax Act came into effect.

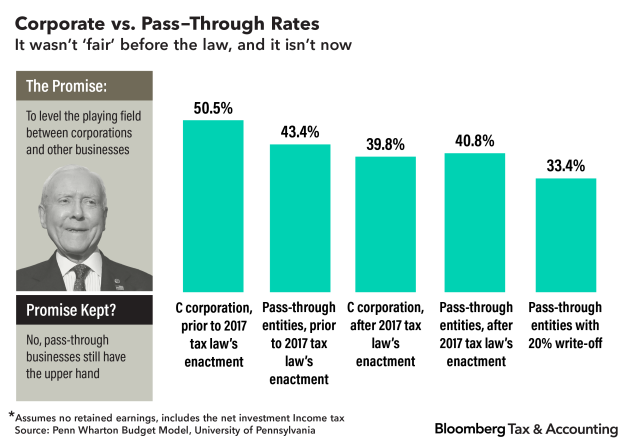

Promise: A level playing field

A company's tax rate depends, among other things, on its structure.

Most companies are structured as pass-through or flow-through, with the owners having individual tax rates and no taxes on the companies themselves.

On the surface, it may seem unfair to cut the corporate tax rate from 35% to 21% while only cutting the top tax rate from 39.6% to 37%. The law therefore provides a special allowance for pass-through owners that allows them to shield up to 20% of their income from these companies from individual taxes.

But it is not that easy to compare the corporate tax rate and the individual tax rate.

After the profits of a C company are taxed at the corporate rate, the remaining profits that go to shareholders are also taxed at the capital gains rate. Depending on how much profit is distributed to these shareholders, the total rate on corporate profits could be significantly higher than the individual tax rates that the transit owners faced prior to the tax law revision. That is still the case, albeit to a lesser extent, with this 20% deduction.

"Only in terms of fairness is there still an advantage to pass-throughs," said Richard Prisinzano, director of policy analysis for the Penn Wharton Budget Model. "It was just reduced."

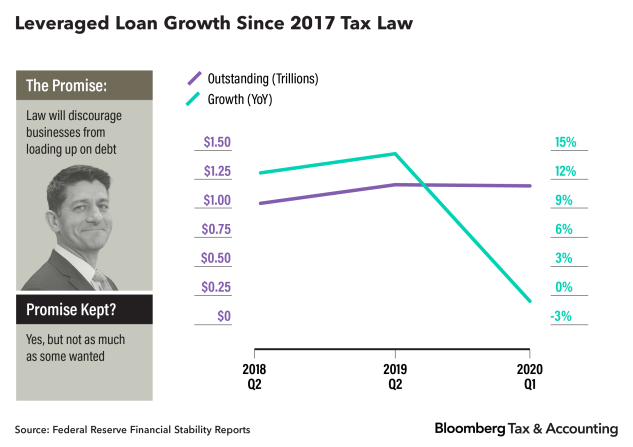

Promise: Less corporate debt

The 2016 blueprint of then House Speaker Paul Ryan, which served as the framework for initial talks on tax reform, highlighted the need to scrap measures that incentivized companies to increase their debt burdens. Ryan's ideal solution – a complete elimination of depreciation on net interest expense – did not end up in the final package.

The law restricted corporations' ability to use the interest they pay on loans to lower their tax burden, and lowering corporate interest rates made interest deductions less valuable. The interest depreciation limit includes a number of exceptions and opt-outs. While it is set to be narrowed down over the next year, lobbying is underway to prevent that from happening.

Many companies took advantage of an inflow of cash in 2018 to pay off debt. But with the help of historically low interest rates, the private sector debt frenzy certainly didn't end with the law.

Janet Yellen, who was confirmed as Treasury Secretary on Monday, criticized American companies at the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic for having carried an "enormous" mountain of debt into the crisis.

"I think they have borrowed excessively by issuing corporate bonds and leveraged loans, many of them with poor credit confidence and poor underwriting," said Yellen. "Even if a company avoids defaulting, heavily indebted companies usually cut sharply on investments and hires, which makes recovery difficult."