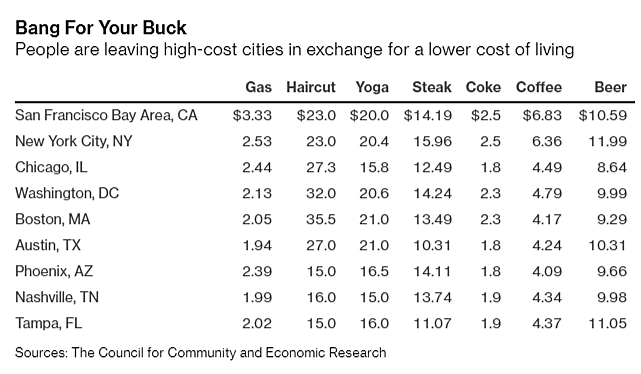

As my Cato colleague Chris Edwards and I have been documenting here recently, COVID-19 has accelerated the longer‐term migration of many Americans from expensive cities like New York and San Francisco to places with lower taxes and a lower overall cost of living. Examining changes to LinkedIn members’ zipcodes and various cost‐of‐living metrics, Bloomberg’s Misyrlena Egkolfopoulou today provides more evidence of the “Expensive Exodus”:

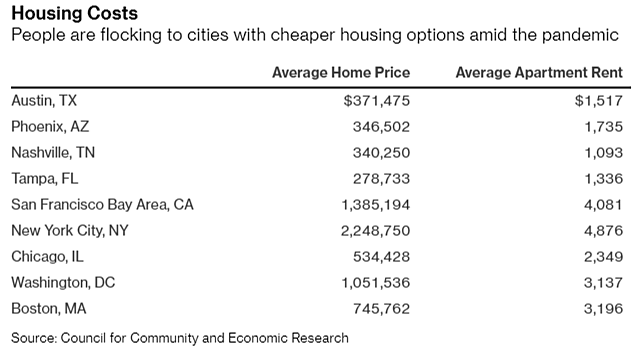

Citing these and other data, as well as various anecdotes, Egkolfopoulou concludes that cost of living — especially housing — is playing a “major role” in movers’ decisions:

(S)ome of the most expensive urban areas (are) seeing the biggest population loss versus previous years. Outbound moves in the Bay Area rose 8% in May‐September, compared with the same period in 2019, while Seattle and New York both experienced a 7% increase… Meanwhile, Jacksonville, Raleigh, Charlotte, Nashville and Phoenix were among cities with the most inbound moves, according to the Webster Pacific and United Van Lines data.

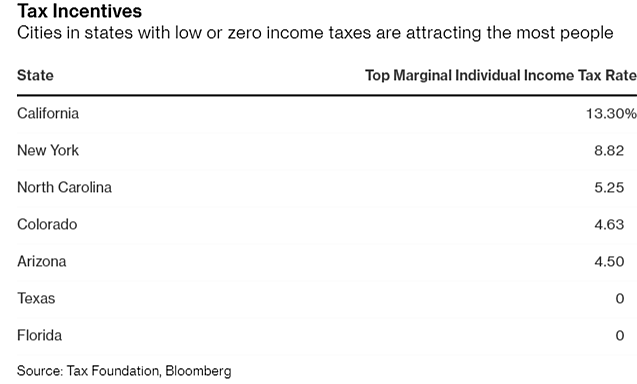

She adds that tax policy is another important driver:

…Covid‐19 is accelerating a decision that was being made by scores of others even before the pandemic. While cost of living, lifestyle, property prices and jobs influence the moves, the cities that are attracting the most people are in states with lower or zero local income tax rates.

As Edwards and I have noted, these migration trends pre‐dated COVID-19 but have been amplified for wealthier Americans who are more likely to be working from home during the pandemic and have the means to change addresses relatively quickly. While their departure from expensive “superstar” cities has been cheered by some, the University of Toronto’s Richard Florida warns that this trend could have a serious impact on local budgets: “A whopping 80% of New York City’s income tax revenue, according to one estimate, comes from the 17% of its residents who earn more than $100,000 per year. If just 5% of those folks decided to move away, it would cost the city almost one billion ($933 million) in lost tax revenue.” He remains optimistic about superstar cities’ long‐term prospects but warns that, if these places’ “policies don’t change, their budgets will suffer in the meantime, and their least‐advantaged people and neighborhoods will bear the brunt of it as budget cuts and austerity measures eliminate key services.” Because Florida blames much of the current exodus on the 2017 federal tax law’s limitations on deductions for state and local taxes (SALT), which once gave high‐tax cities “a fighting chance against their lower‐tax rivals,” he suggest that city and state governments develop “new revenue models that account for the locations of both the people and their businesses” to counter the “effect of new remote technology on state and local taxes.”

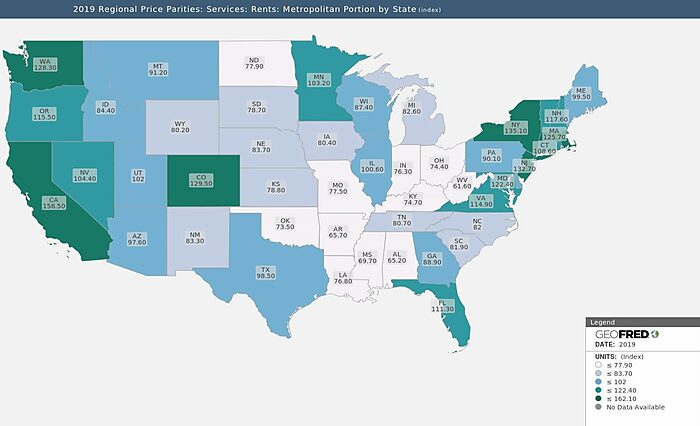

However, that approach would seem to ignore the many non‐tax reasons why wealthier Americans — now unburdened by a physical office — are leaving costlier places (though the SALT deduction is indeed likely playing a role). Most notable in this regard is housing: beyond the home price data noted above, for example, St. Louis Fed’s Regional Price Parity (RPP) indices, which allow economists to compare living costs across state metro areas, shows that rent differences between out‐migration states and in‐migration states are in most cases quite substantial:

A novel “revenue” solution also elides the far more straightforward policy approach that high‐cost states and cities could undertake: attacking costs head‐on through less‐punitive taxes (on both income and goods), less regulation (especially for housing), better governance, and more personal freedom. As Edwards notes in his 2018 paper, such policies could not only dissuade current residents from leaving, but also attract new people and investments.

These places can’t change their weather, but they can certainly improve their economic climate.