The OECD on Feb. 11, 2020, released its transfer pricing financial transactions guidance, which addresses a variety of issues including whether intercompany financing is debt or equity and what represents an arm’s-length interest rate. Economists focus on what this guidance refers to as the pricing issue, that is, the evaluation of the arm’s-length interest rate.

A standard model for evaluating whether an intercompany interest rate is arm’s-length can be seen to have two components: the intercompany contract and the credit rating of the related-party borrower. Properly articulated intercompany contracts stipulate:

- The date of the loan,

- The currency of denomination,

- The term of the loan, and

- The interest rate.

The first three items allow the analyst to determine the market interest rate of the corresponding government bond. This intercompany interest rate minus the market interest rate of the corresponding government bond can be seen as the credit spread implied by the intercompany loan contract.

The OECD guidance provides a lengthy discussion titled “The Accurate Delineation of the Transaction.” A clear intercompany contract is only part of the considerations, as this discussion also raises issues which the authorities may explore in any attempt to recast intercompany debt as equity, thereby denying the interest deduction. The pricing issue, on the other hand, could only limit the interest deduction by insisting on a lower intercompany interest rate to an arm’s-length rate.

The OECD guidance provides a lengthy discussion on the evaluation of an appropriate credit spread. Even if a consensus is reached on the difficult issue with respect to the credit rating, being able to translate this letter-grade credit rating into a numerical credit spread requires reliable and timely data on credit spreads. We shall explore certain considerations with respect to the debt-versus-equity issue as well as potential pricing issues in a recent U.K. litigation and four previous U.S. cases.

BlackRock v. HMRC

The taxpayer prevailed in BlackRock HoldCo 5 LLC v. The Commissioners for Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs (HMRC) on Nov. 3, 2020, in a litigation where HMRC attempted to deny intercompany interest deductions of nearly $200 million per year.

BlackRock agreed to pay $13.5 billion to acquire Barclays’ investment management business in 2009. Part of the financing of this acquisition involved a $4 billion intercompany loan, which was structured by tax advisers from Ernst & Young. The structure involved several affiliates and was referred to as U.S./U.K. sandwich. The intent was to have in the United Kingdom an interest rate deduction that was not recognized as U.S. taxable income. This type of hybrid mismatch was a key issue in the OECD’s Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) Action Plan 2.

The intercompany loan involved four tranches with different maturities and different interest rates. We shall pose a simple version of an intercompany loan that roughly captures this more-involved loan structure. Let’s assume an interest loan with the following features:

- Date: July 1, 2010

- Amount: $4 billion

- Term: 5 years

- Interest rate: Fixed 5%.

On that date, the interest rate on 5-year U.S. government bonds was 1.8%, so the credit spread implied by the original intercompany interest rate was 3.2%. After HMRC started its audit of this loan structure, the interest rates were lowered by approximately 1.5%. If both parties agreed to a 3.5% interest rate, the implied credit spread would be 1.7%.

As the litigation was over whether to deny the entire intercompany deduction, the expert witnesses focused not on the arm’s-length interest rate but rather on how the intercompany loan should have been structured. In particular, both experts noted that third-party lenders may have required protective covenants in exchange for a reasonable interest rate.

The experts disagreed as to whether a third-party borrower would have accepted such covenants. The taxpayer’s expert argued that a third-party borrower would have accepted covenants even though they limit the financial flexibility for the borrower. The tax authority’s expert disagreed, arguing that these covenants would be too complex and costly to the borrower, even though BlackRock had agreed to similar covenants in its third-party revolving credit facility. For third-party loans, a lack of covenants places the lender at greater risk of default. Multinationals that wish to charge their related-party borrowers higher intercompany interest rates have argued that a lack of covenants for the intercompany loan suggests a lower credit rating and hence a higher interest rate under arm’s-length pricing.

The intercompany loan in the BlackRock litigation was similar to that in Chevron Australia Holdings Pty Ltd v. Commissioner of Taxation, where the loan did not have covenants. The Australian Tax Office (ATO) only argued the pricing issue, insisting that the 4.14% loan margin should be lowered to 1.44%. The Chevron representatives argued an “orphan theory” where the intercompany debt was seen as subordinated debt. The Australian court rejected this approach, arguing that third-party lenders would have relied on implicit support from the parent corporation. The ATO position was that the appropriate credit rating was BBB.

We noted that in the BlackRock litigation, the original intercompany interest rate was consistent with a 3.2% credit spread while the revised intercompany interest rate was consistent with a 1.7% credit spread. The high credit spread would be consistent with a credit rating of BB, while the lower credit spread would be consistent with a credit rating of BBB.

This argument for high credit spreads is often challenged by tax authorities for reasons noted in the OECD transfer pricing guidelines on financial transactions under paragraphs 10.62 to 10.86. Paragraph 10.86 states:

“There may be less information asymmetry between entities (that is, better visibility) in the intragroup context than in situations involving unrelated parties. Intra-group lenders may choose not to have covenants on loans to associated enterprises, partly because they are less likely to suffer information asymmetry and because it is less likely that one part of an MNE group would seek to take the same kind of action as an independent lender in the event of a covenant breach, nor would it usually seek to impose the same kind of restrictions.”

The taxpayer’s expert argued that no guarantee was needed because of the implicit support of the parent company. The OECD’s transfer pricing guidance on financial transactions notes the role of implicit support. The intercompany loans’ lack of covenants was not seen as a reason to disregard the intercompany loans by this court decision but they may not have been an excuse to argue for a high credit spread.

Scottish Power and Pepsi Puerto Rico

NA General Partnership & Subsidiaries v. Commissioner involved a U.S. affiliate of Scottish Power plc that incurred $4.9 billion in intercompany financing related to the acquisition of PacifiCorp in November 1999.The U.S. affiliate, NA General Partnership, took out two intercompany loans:

- A $4 billion fixed-interest-rate loan at 7.3% with the term extending to November 2011; and

- A $0.9 billion floating-rate loan set at the LIBOR plus a loan margin of 0.55%.

Interest rates during November 1999 were approximately as follows:

- Interest rates on 10-year U.S. government bonds were 6.2%;

- Interest rates on 20-year U.S. government bonds were 6.5%;

- The 12-month LIBOR was 6.25%; and

- Interest rates on one-year government bonds were 5.7%.

The latter two interest rates suggest a TED spread equal to 0.55% and a credit rating on the floating rate loan equal to the sum of this TED spread and the loan margin for a total credit spread of 1.1%. The TED spread is the difference between the interest rates on interbank loans and on short-term U.S. government debt. If we interpolate the interest rates on 10-year and 20-year government bonds, we can infer that a 12-year government bond (if it existed) would have an interest rate equal to 6.25%. As such, the implied credit spread on the fixed interest rate would be 1.05%. These credit spreads would be consistent with a credit rating of A. At the time of the acquisition, PacifiCorp had a credit rating of A.

While these intercompany financing instruments were treated as debt for U.S. purposes, they were treated as equity contributions under U.K. tax law. The IRS objected to this hybrid financing arrangement and sought under Section 385 to have this financing treated as equity for purposes of U.S. tax. The IRS lost this case.

The positions of the expert witnesses were interesting in their assertions for credit ratings and the arm’s-length interest rate. The intercompany financing increased the portion of the assets being financed by debt, which should lead to a lower credit rating. Robert Mudge, testifying as an expert witness for the IRS, argued that the U.S. affiliate had a credit rating of B, while William Chambers, testifying for the taxpayer, argued that the affiliate had a credit rating of BB+. A credit rating of B, if credible, would suggest a credit spread near 4.75% and hence an interest rate near 11% for the fixed-interest-rate loan. The court, however, accepted the Chambers assertion that the credit rating was BB+, which implied a credit spread near 2.25% and an interest rate near 8.5%.

One might wonder why the IRS argued for a lower credit rating. As the court noted:

“Respondent argues, relying on his expert Mr. Mudge, that NAGP would have likely been rated below investment grade by an independent rating agency such as Standard & Poor’s (S&P), and that this establishes NAGP was thinly capitalized.”

The IRS argued that the financing was equity and not debt because of this thin capitalization. The court rejected this contention and ultimately agreed that the intercompany financing was debt for purposes of U.S. tax law. One might question why the U.K. government did not seek an increase in the intercompany rate based on the testimony of Mr. Chambers. Of course, the fact that the financing was treated as equity for U.K. purposes meant that no U.K. income was recognized.

PepsiCo Puerto Rico Inc. v. Commissioner involved an attempt by the IRS to recast equity in an affiliate into intercompany debt. The issue in this litigation was a hybrid financial instrument where the intercompany financing was treated as debt for purposes of Dutch tax law but treated as equity under U.S. tax law. While the Dutch tax authority accepted the treatment, the IRS did not. However, the IRS lost its bid to treat the intercompany financing as an intercompany loan.

The intercompany debt for the Dutch affiliate was $4 billion issued on Sept. 1, 1996. The interest rate was initially set at the greater of (1) the six-month LIBOR (London Interbank Offered Rate) on the relevant date plus 2.3% or (2) 7.5%. After the fall of short-term interest rates during the 2001 recession, the terms were amended to eliminate the 7.5% minimum. The six-month LIBOR over this period averaged 4.24%, which meant that the intercompany interest rate averaged 6.54%. The six-month Treasury bill rate averaged 3.76% over this period, which means the average six-month TED spread was 0.48% and the average credit spread was 2.78%.

This credit spread would be seen as reasonable if the Dutch affiliate’s credit rating were BB. The credit rating for the parent company was A, which would suggest that the Dutch tax authority could have challenged this intercompany interest rate if an implicit support argument suggested a higher credit rating than BB for the borrowing affiliate.

Two U.S. Corporate Inversion Cases

The taxpayer in Tyco Electronics v. Commissioner moved its corporate headquarters to Bermuda in 1997, and the taxpayer in Ingersoll-Rand v. Commissioner incorporated in Bermuda in 2002. Both of these companies used intercompany debt to substantially reduce its U.S. taxable income. Ely Portillo describes the IRS challenge of Ingersoll-Rand:

“The company’s Bermuda parent company loaned billions of dollars to its U.S. subsidiary. The U.S. subsidiary then paid back the loan, with interest, creating profits in tax-free Bermuda for the parent company and tax-deductible interest for the U.S. company. The money was routed through Luxembourg, Hungary and Barbados. The U.S. has tax treaties with each of those countries, exempting loan repayments coming from the U.S. The IRS said it wants to treat the payments as if they were made directly to Bermuda, rather than routed through treaty countries. That means the payments would be subject to a 30 percent tax.” (Portillo, IRS Fights Ingersoll-Rand Over Offshore Money Routing, Charlotte Observer (Sept. 27, 2014))

Patrick Temple-West notes the litigation regarding Tyco:

Tyco is challenging a $1 billion tax bill assessed by the IRS based on its view that cash transfers carried out within the multinational company were not debt payments, but taxable dividends, according to U.S. Tax Court documents. (Temple-West, IRS Takes on Tyco in U.S. Tax Court Debt-vs-Equity Dispute, Reuters (Aug. 7, 2013))

The IRS also tried to use Section 385 to recast the intercompany loans of Ingersoll-Rand as equity. During 2002, the various foreign affiliates of Ingersoll-Rand loaned its U.S. affiliate $8.9 billion. These intercompany loans had 10-year terms with a fixed interest rate equal to 11%. Interest rates on 10-year U.S. government bonds during the first half of 2002 varied from 4.75% to 5.45%, averaging 5.1% during this period. The 11% intercompany rate was consistent with a credit spread in excess of 5.5%.

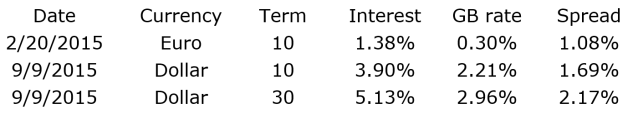

Table 1 presents key information on Ingersoll-Rand’s corporate bond offerings since 2014 including the date of the bond offering, the term to maturity, and the interest rate. All corporate bonds were denominated in U.S. dollars. Table 1 also shows the corresponding U.S. government bond (GB) rate and the credit spread for each bond offering. These spreads average approximately 1.1%, which is indicative of a credit rating of A.

Table 1: Ingersoll-Rand’s Corporate Bond Offerings

Of course, the credit rating back in 2002 may have differed and the credit rating of an affiliate may differ from that of the overall corporation. Given the more than 5.5% credit spread implied by the 11% intercompany interest rate, it is reasonable to believe the IRS could have challenged the arm’s-length nature of such a high interest rate.

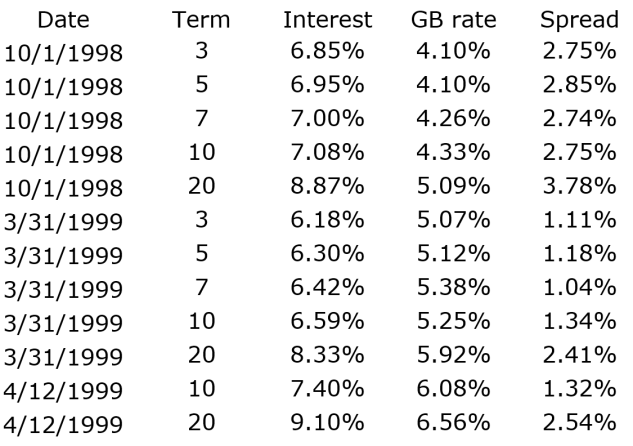

The Tyco petitions to the Tax Court show that there were several intercompany loans at issue. We shall focus on the intercompany loans issued on Oct. 1, 1998, March 31, 1999, and Aug. 12, 1999. On each date, there were several fixed-interest-rate loans with varying maturities. Table 2 presents the key information on these loans. The implied credit spread equals the difference between the intercompany interest rate and the interest rate on the corresponding government bond.

The implied spreads for the Oct. 1, 1998, loans were generally less than 3%, while the implied spreads for the March 31, 1999, loans were generally just over 1%. The implied spreads on the 20-year terms, however, were somewhat higher.

The petitions note two other sets of intercompany loans not captured by Table 2. One set was a sequence of 13-year term loans with a fixed interest rate equal to 7.08%. During August 1998, the average interest rate in 10-year government bonds was 5.36%. The implied credit spread was therefore near 1.7%. On Aug. 18, 1999, intercompany loans were issued where the interest rate was based on 12-month LIBOR plus a 1.25% margin. On that date, the 12-month LIBOR rate was 6.03% while the interest rate on one-year government bonds was 5.19%. As such, the intercompany interest rate was 7.28%, which exceeded the one-year government bond rate by 2.09%.

Whether these intercompany interest rates and implied credit spreads are reasonable depends on what the appropriate credit rating of the rated-party borrowers was. Table 3 presents certain key information with respect to the issuance of corporate bonds by Tyco International during 2015. These third-party interest rates imply credit spreads roughly similar to the credit spreads implied by the 1999 intercompany loans.

The intercompany loans issued in late 1998 have higher implied credit spreads. A defense of these higher intercompany interest rates would require evidence that the appropriate credit rating for the U.S. borrowing affiliate should be BB. An IRS challenge to these intercompany interest rates would have to demonstrate that the appropriate credit rating was investment grade in late 1998. Even if such a case could have been made, the reduction in intercompany interest rates would have been modest.

Table 2: Tyco International’s Intercompany Debt

Table 3: Tyco International 2015 Corporate Bond Offerings

Concluding Comments

The OECD transfer pricing guidance on financial transactions discusses both debt-versus-equity issues as well as the pricing of intercompany loans. We have noted several IRS attempts to reclassify intercompany debt as equity in order to deny intercompany deductions. In many cases, the IRS does not succeed in recharacterizing debt as equity.

The two celebrated corporate inversion cases where debt-versus-equity concerns were raised involved intercompany loan rates well above the interest rates on the corresponding government bond rates. If the IRS could have argued that the appropriate credit rating for the borrower affiliate was investment grade, a case could be made that the intercompany interest rate exceeded the arm’s-length rate.

HMRC challenged the intercompany financing in the BlackRock litigation hoping to reclassify debt as equity in order to eliminate approximately $200 million per year in interest deductions. While this challenge failed, the intercompany interest rate was lowered such that the intercompany deduction was lowered to approximately $140 million. It is instructive that the taxpayer’s argument for debt rather than equity classification included an acceptance of the implicit support position in prior litigations. This position supports an argument for a high credit rating for the borrower affiliate, which would imply a lower arm’s-length interest rate.

This column doesn’t necessarily reflect the opinion of The Bureau of National Affairs Inc. or its owners.

Author Information

Harold McClure has been involved in transfer pricing as an economist for 25 years.